PARASOPHIA – Institutional Engagement

by Takahashi Satoru

2015.03.27

Takahashi Satoru

PARASOPHIA: Kyoto International Festival of Contemporary Culture 2015 is burdened with all manner of expectations. Faced with these expectations, however, it continues to maintain a willingness to nonsensically betray them. Faced with the question, Why Kyoto? it wants to answer, Why not? The plausible justification of place is fraught with danger.

This year, the organizers have gone as far as eschewing the use of the word “art” in the English title, preferring instead the words “contemporary culture.” However, if this is no more than an offer of resistance to the international exhibitions and consumption culture that are being reproduced on a global scale, then it is simply tedious. “In order to cure a disease, one must first cure the environment around medical treatment itself” is a phrase used in the “institutional psychotherapy” practiced in countries like France and Japan. One could say this is an attempt to review the allocation methods of knowledge/authority/expertise within health care and to rebuild the institutional relationship among patients/doctors/nurses (by having patients use knives to teach doctors how to cook, for example). In art, too, a similar “institutional” approach of rearranging the institutional environment surrounding art and the division of the roles of creating, viewing, writing, selling and teaching, leading to the redistribution of knowledge/authority/expertise, is possible.

PARASOPHIA has an affinity to the encyclopedias of the 18th century, reference works that “could be consulted on all matters concerning the arts and sciences and which would serve as much to guide those who have the courage to work for the instruction of others as to enlighten those who are only teaching themselves” (the quotation is from the Preliminary Discourse to the Encyclopedia of Diderot). When these encyclopedias were introduced to Japan in the Meiji period, they were referred to in Japanese as hyakugaku renkan (literally “chains of 100 branches of learning”), making clear the meaning that they were books to be used as tools to grasp in a chain-like fashion the knowledge/expertise required to form the concept of “man” that developed in the modern era. In the 21st century, when there is a need to reconstruct the modern concept of man itself, hyakugaku renkan is being questioned anew from a different perspective. No doubt the idea behind PARASOPHIA is to build a platform to facilitate this.

As a practical advantage in “institutional” terms, Kyoto is home to five art universities, several famous non-specialist universities including Kyoto University, Doshisha University and Ritsumeikan University, various traditional arts and crafts organizations, as well as a number of private research institutes. As for government, new projects are being pursued on the basis of cooperation among industry, government and academia. In this sense, PARASOPHIA is a good opportunity to “explore the possibilities of a platform for art/research/education beyond the confines of specialist organizations or location.” In a paradoxical manner of speaking, the use of unfamiliar contemporary art in the form of PARASOPHIA as a “temporary vessel” will make it possible to experiment with transferring cross-sectionally and in the public domain “worthless knowledge/expertise” that has been confined to separate boxes and dispersed. However, regulars who belong to institutions will not be the players because they shut themselves in ivory towers and fail to doubt the limitations of their institutions. Essentially, the key is to enable independent entities to engage as players irrespective of race, gender, age and occupation. Also, to secure in advance means of guaranteeing the time and funds needed to achieve this. What if within the “neutral space” that is PARASOPHIA, “temple schools” and studios and seminar rooms stood side by side and we were able to establish the kinds of classes and marketplaces/universities where various subjects could come together freely without identification in an atmosphere akin to that of a night fair at a Shinto shrine? The marketplaces known as “agora” where Socrates captivated youngsters and waged battles of words were at the same time public domains where various things were bought and sold and where even foreigners could come and go as they pleased. Is the provision of this kind of space something that the “institutional international exhibition” PARASOPHIA can facilitate?

Just to be sure, let me stress that “engagement” does not refer to the kind of participatory art found in contemporary art textbooks. With most of this kind of art, it is not that the audience wants to participate; rather, the artist needs the audience to participate. It is the exhibition of art as justification in the sense that by getting people who happen to be visiting an art museum to participate for a moment or two they are signaling that they are engaged with the world at large. But can this really be called participation? There are problems with the word “participatory” itself, and so personally I prefer to use the word “engagement.” This means coming face-to-face at the level of a proper name relationship not for the limited period of an exhibition but on a more long-term basis. Unless people meet in the context of this kind of engagement and on the basis of a different perspective in which local problems are dealt with globally and global problems dealt with locally, the participatory approach is doomed to become something meaningless with no connection to reality.

“still moving,” an exhibition organized at a separate venue in the Suujin district, appears to show an awareness of the issues outlined above. (The title, meaning “in the process of house-moving,” is similar to that of a previous project by Artistic Director Kohmoto Shinji, “STILL\MOVING,” except the backslash has been removed.) What the artists sought to achieve with their approach to the Suujin district was quite different from the irrelevancies of Yomota Inuhiko’s class president-like remark, quoted in Asada Akira’s review, “How is it that you can live in Kyoto and not know about the Suujin district?” and of the suggestion, also in Asada’s review, that going to visit Suujin after seeing Yanagi Miwa’s vacuous stage trailer in front of the Kyoto Municipal Museum of Art would deepen one’s understanding of the former. Rather, the aim was to reclaim a perspective different from that of Kyoto tourism. At the same time, it was to reposition the relocation idea/plan being pursued abstractly by the university/government in the context of an international exhibition, transposing it to an open environment that includes the local community and foreigners (the Hoefner/Sachs Suujin Park project was also a part of this). This writer was involved as a participating artist in installing Ornament and Crime: Sense/Common, which also has a Suujin connection, at the Kyoto Municipal Museum of Art (the Senkaku Islands/Takeshima Island were arranged within a blanched courtroom, prison, and what at a glance appeared to be a stereotypical rock garden. Backstage were an aerial photograph of Suujin and an empty map). This was an attempt not to prescribe Suujin within a particular history/space, but to approach it on the basis of its connection to the alarming nationalism and nonsense unfolding at a regional level.

On May 9 and 10, which coincides with the closing of PARASOPHIA, a spring festival will be held in the Suujin district. It commemorates a time when local residents carried an independent portable shrine that they built themselves because they were not permitted to become parishioners of established Shinto shrines. It also probably serves as a proposal for a technique for living a better life as opposed to accepting the saving of changes to history. In order to understand this, one needs to give careful attention not only to the voices audible and the images visible in the “here and now,” but also to inaudible voices from the invisible yonder. This holds true for the ideas behind PARASOPHIA, which has only just begun. The seeds of possibility are surely beginning to germinate.

Takahashi Satoru is a participating artist in PARASOPHIA and a professor at Kyoto City University of the Arts. He was unofficially involved in concept development, venue selection etc. prior to the startup of the festival.

PARASOPHIA: Kyoto International Festival of Contemporary Culture 2015 | REALKYOTO | (Index of related articles)

Review : Asada Akira: PARA-PARASOPHIA: On the sidelines at the Kyoto International Festival of Contemporary Culture

Fukunaga Shin: For the First Kyoto International Festival of Contemporary Culture

Takahashi Satoru: PARASOPHIA – Institutional Engagement

—

Official Site : PARASOPHIA: Kyoto International Festival of Contemporary Culture 2015

PARASOPHIA: Kyoto International Festival of Contemporary Culture 2015 is burdened with all manner of expectations. Faced with these expectations, however, it continues to maintain a willingness to nonsensically betray them. Faced with the question, Why Kyoto? it wants to answer, Why not? The plausible justification of place is fraught with danger.

This year, the organizers have gone as far as eschewing the use of the word “art” in the English title, preferring instead the words “contemporary culture.” However, if this is no more than an offer of resistance to the international exhibitions and consumption culture that are being reproduced on a global scale, then it is simply tedious. “In order to cure a disease, one must first cure the environment around medical treatment itself” is a phrase used in the “institutional psychotherapy” practiced in countries like France and Japan. One could say this is an attempt to review the allocation methods of knowledge/authority/expertise within health care and to rebuild the institutional relationship among patients/doctors/nurses (by having patients use knives to teach doctors how to cook, for example). In art, too, a similar “institutional” approach of rearranging the institutional environment surrounding art and the division of the roles of creating, viewing, writing, selling and teaching, leading to the redistribution of knowledge/authority/expertise, is possible.

PARASOPHIA has an affinity to the encyclopedias of the 18th century, reference works that “could be consulted on all matters concerning the arts and sciences and which would serve as much to guide those who have the courage to work for the instruction of others as to enlighten those who are only teaching themselves” (the quotation is from the Preliminary Discourse to the Encyclopedia of Diderot). When these encyclopedias were introduced to Japan in the Meiji period, they were referred to in Japanese as hyakugaku renkan (literally “chains of 100 branches of learning”), making clear the meaning that they were books to be used as tools to grasp in a chain-like fashion the knowledge/expertise required to form the concept of “man” that developed in the modern era. In the 21st century, when there is a need to reconstruct the modern concept of man itself, hyakugaku renkan is being questioned anew from a different perspective. No doubt the idea behind PARASOPHIA is to build a platform to facilitate this.

As a practical advantage in “institutional” terms, Kyoto is home to five art universities, several famous non-specialist universities including Kyoto University, Doshisha University and Ritsumeikan University, various traditional arts and crafts organizations, as well as a number of private research institutes. As for government, new projects are being pursued on the basis of cooperation among industry, government and academia. In this sense, PARASOPHIA is a good opportunity to “explore the possibilities of a platform for art/research/education beyond the confines of specialist organizations or location.” In a paradoxical manner of speaking, the use of unfamiliar contemporary art in the form of PARASOPHIA as a “temporary vessel” will make it possible to experiment with transferring cross-sectionally and in the public domain “worthless knowledge/expertise” that has been confined to separate boxes and dispersed. However, regulars who belong to institutions will not be the players because they shut themselves in ivory towers and fail to doubt the limitations of their institutions. Essentially, the key is to enable independent entities to engage as players irrespective of race, gender, age and occupation. Also, to secure in advance means of guaranteeing the time and funds needed to achieve this. What if within the “neutral space” that is PARASOPHIA, “temple schools” and studios and seminar rooms stood side by side and we were able to establish the kinds of classes and marketplaces/universities where various subjects could come together freely without identification in an atmosphere akin to that of a night fair at a Shinto shrine? The marketplaces known as “agora” where Socrates captivated youngsters and waged battles of words were at the same time public domains where various things were bought and sold and where even foreigners could come and go as they pleased. Is the provision of this kind of space something that the “institutional international exhibition” PARASOPHIA can facilitate?

Just to be sure, let me stress that “engagement” does not refer to the kind of participatory art found in contemporary art textbooks. With most of this kind of art, it is not that the audience wants to participate; rather, the artist needs the audience to participate. It is the exhibition of art as justification in the sense that by getting people who happen to be visiting an art museum to participate for a moment or two they are signaling that they are engaged with the world at large. But can this really be called participation? There are problems with the word “participatory” itself, and so personally I prefer to use the word “engagement.” This means coming face-to-face at the level of a proper name relationship not for the limited period of an exhibition but on a more long-term basis. Unless people meet in the context of this kind of engagement and on the basis of a different perspective in which local problems are dealt with globally and global problems dealt with locally, the participatory approach is doomed to become something meaningless with no connection to reality.

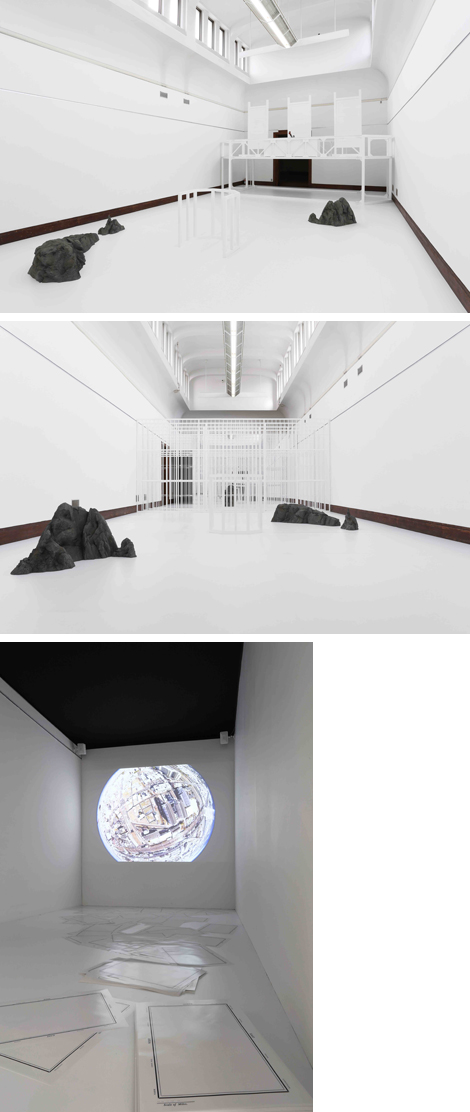

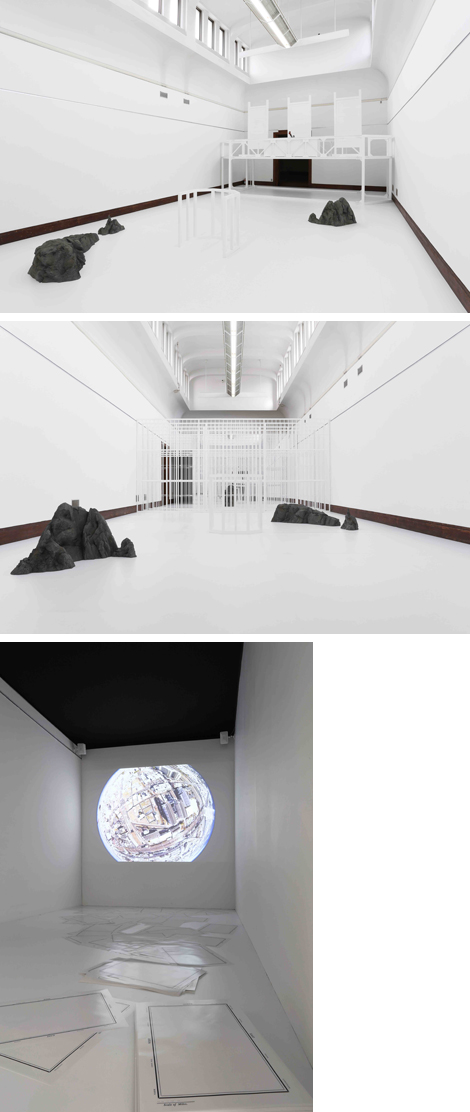

“still moving,” an exhibition organized at a separate venue in the Suujin district, appears to show an awareness of the issues outlined above. (The title, meaning “in the process of house-moving,” is similar to that of a previous project by Artistic Director Kohmoto Shinji, “STILL\MOVING,” except the backslash has been removed.) What the artists sought to achieve with their approach to the Suujin district was quite different from the irrelevancies of Yomota Inuhiko’s class president-like remark, quoted in Asada Akira’s review, “How is it that you can live in Kyoto and not know about the Suujin district?” and of the suggestion, also in Asada’s review, that going to visit Suujin after seeing Yanagi Miwa’s vacuous stage trailer in front of the Kyoto Municipal Museum of Art would deepen one’s understanding of the former. Rather, the aim was to reclaim a perspective different from that of Kyoto tourism. At the same time, it was to reposition the relocation idea/plan being pursued abstractly by the university/government in the context of an international exhibition, transposing it to an open environment that includes the local community and foreigners (the Hoefner/Sachs Suujin Park project was also a part of this). This writer was involved as a participating artist in installing Ornament and Crime: Sense/Common, which also has a Suujin connection, at the Kyoto Municipal Museum of Art (the Senkaku Islands/Takeshima Island were arranged within a blanched courtroom, prison, and what at a glance appeared to be a stereotypical rock garden. Backstage were an aerial photograph of Suujin and an empty map). This was an attempt not to prescribe Suujin within a particular history/space, but to approach it on the basis of its connection to the alarming nationalism and nonsense unfolding at a regional level.

Sugiyama Masayuki, Which has come—, 2015.

Installation view at the exhibition still moving.

Photo courtesy still moving.

Hoeffner/Sachs, Suujin Park, 2015.

Installation view at PARASOPHIA: Kyoto International Festival of Contemporary Culture.

Photo courtesy PARASOPHIA Organizing Committee.

Kurashi Keiko & Takahashi Satoru, Ornament and Crime: Sense/Common, 2015.

Photo courtesy PARASOPHIA Organizing Committee.

On May 9 and 10, which coincides with the closing of PARASOPHIA, a spring festival will be held in the Suujin district. It commemorates a time when local residents carried an independent portable shrine that they built themselves because they were not permitted to become parishioners of established Shinto shrines. It also probably serves as a proposal for a technique for living a better life as opposed to accepting the saving of changes to history. In order to understand this, one needs to give careful attention not only to the voices audible and the images visible in the “here and now,” but also to inaudible voices from the invisible yonder. This holds true for the ideas behind PARASOPHIA, which has only just begun. The seeds of possibility are surely beginning to germinate.

Takahashi Satoru is a participating artist in PARASOPHIA and a professor at Kyoto City University of the Arts. He was unofficially involved in concept development, venue selection etc. prior to the startup of the festival.

(March 29, 2015)

(English translation: Pamela Miki Associates)(Publication of the English version: April 25, 2015)

—PARASOPHIA: Kyoto International Festival of Contemporary Culture 2015 | REALKYOTO | (Index of related articles)

Review : Asada Akira: PARA-PARASOPHIA: On the sidelines at the Kyoto International Festival of Contemporary Culture

Fukunaga Shin: For the First Kyoto International Festival of Contemporary Culture

Takahashi Satoru: PARASOPHIA – Institutional Engagement

—

Official Site : PARASOPHIA: Kyoto International Festival of Contemporary Culture 2015