Review

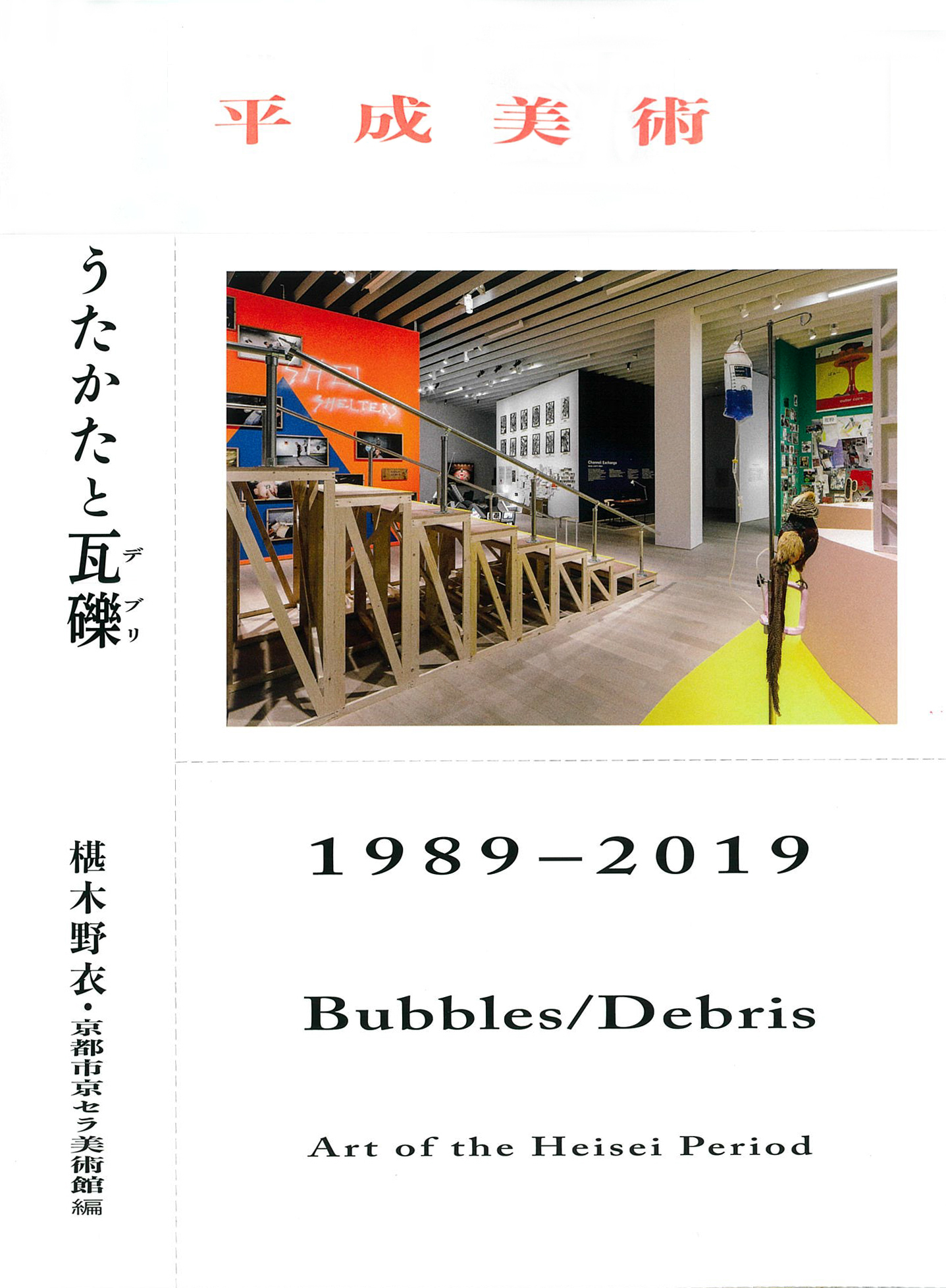

Bubbles / Debris: Art of the Heisei Period 1989–2019

Text: Fukunaga Shin

In 1999, Sawaragi Noi curated the exhibition“Ground Zero Japan” at Art Tower Mito. What made “Ground Zero Japan” so radical was that it was actually the practice/application of Sawaragi’s 1998 critical essay Nihon/Gendai/Bijutsu (Japan/Modernity/Art). Revolutionary, hitherto unheard-of ideas like this acrobatic connecting of the disconnect between art criticism and art exhibition (work) are typical of Sawaragi Noi.

Sawaragi Noi Nihon/Gendai/Bijutsu [Shinchosha]

Throughout his prolific early career, beginning with Simulationism (1991), his first collection of critical essays on art, Sawaragi reliably offered up analysis of a Japanese contemporary art (and art criticism) thoroughly conditioned by Japan’s acceptance of western and in particular American culture. Invariably what would start to appear was a mirage-like “contemporary art” that despite attempts at relativizing, would then mysteriously vanish. So what is the true nature of Japanese “contemporary art,” stuck in a vicious cycle of collapse and endless circularity?

In looking back on the just over thirty years of the Heisei era, “Bubbles / Debris: Art of the Heisei Period 1989–2019” focuses not on individual artists but groups, collectives, pluralities of people. The idea of seeing the “collective” as the distinguishing feature of Heisei art was new to me, a tad peculiar even, but this is exactly the sort of thing where Sawaragi comes into his own. Reading his writing one gets a sense that no matter how odd a thing may be, he will claim to have thought the same right from the start. Sawaragi can rightfully be described as the possessor of magical powers of persuasion, and is a highly creative critic. (In contrast to most critics, who in their language tend toward passivity, restraint, and over-sensitivity to the interests of the players involved, Sawaragi uses language boldly, soaringly, and if occasionally laughed at, never fails to give the reader the experience of unexpected discovery. Pulling punches is not his style.)

The start of “Bubbles / Debris: Art of the Heisei Period 1989–2019” is dominated by a giant “History of Heisei” chronology of the era, with most of the exhibition space located behind this. Having here divided its groups and pluralities into three chronological periods, in compositional terms the exhibition then proceeds to invalidate these same divisions to present, as Sawaragi might put it, an “integrated whole.” These three periods are 1) The early Heisei years around 1990, starting from the formation of band-style artist units (such as Complesso Plastico), followed by the bursting of the economic bubble, plunging the economy into prolonged chaos, and making group-type activities, with no economic connections, hard to discern, until 2) when, as if to fill this vacuum, from about 2005 a new movement (exemplified by the likes of Chim↑Pom) starts to become evident that eats its way out of the fine arts system. Then as if to converge with this current, in the few remaining years of the Heisei era, we see 3) the emergence of a trend that could be dubbed “art without artists” in which places for art are found through meetings of individual and individual (eg Suddenly, the view spreads out before us.)

The idea that these group or collective-type art trends in Japan did not necessarily overlap with contemporaneous overseas trends such as artist’s collectives, relational art, and socially engaged art, but were instead more strongly influenced by tough social conditions domestically, is distinctively Sawaragi. Doubtless it was having the “collective” power of humans beyond their individual capabilities demonstrated in the early Heisei years, for example in the new focus on volunteer work following the Hanshin Earthquake, or in a very different way, the Aum Shinrikyo sarin attacks, plus witnessing the dissolution of local communities (for example by mass relocation) following the Tohoku quake and tsunami of 2011, and the disaster at the TEPCO Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Plant, that led Sawaragi to the concept of “a collection of group and collective artists” for this exhibition. It bears repeating that this is indeed an intriguing idea, one most likely arising from an individual critic’s intuition, rather than being the product of research. It would be interesting to see how people receive this “individual” idea.

It appeared however, that people were not especially surprised by Sawaragi’s idea here. Perhaps the exhibition has been put together, dare I say it, a little too well? Certainly there was no time to be bored: we the audience may wander from one work to the next, unthinkingly (or thinking just enough), and enjoying the looking, without tiring. Despite having been actually in different locations, the works never push against each other in any way. For example, with Chim↑Pom and Suddenly, the view spreads out before us., in contrast to the former, who bring an “actual” piece of demolished building into the gallery, the latter have recreated their bridge as a “set” for display. At a glance, the exhibits may seem totally opposite, but both deal with “non-portable realities,” and the fact that in both cases this is done with great attention to detail is made abundantly clear by the “genuine article” and recreated exhibit, and their documentation. Nor has either group of artists forgotten a touch of humor (Suddenly have recreated even the university wall next to the “bridge,” much like a set from a comedy skit: in itself an impressive effort). The resonance when groups or collectives “collect” that can never be apparent in a solo show engenders a harmony of sorts in various places around the venue. Exemplifying this, and I confess making me smile, was the way the sweeping symphony emanating from the booth of Artificial Intelligence Art and Aesthetics Research Group, and the explosive electronic drone music resounding from time to time from the DIVINA COMMEDIA booth, gave the exhibition a strangely harmonious air. The thoughtfulness of the exhibition layout allows us the audience to taste all of interest to us (seeing/reading just the parts we like, the parts that catch our eye), then take our leave. There is nothing whatsoever wrong with this; it’s just that it seems a little too slick, because Sawaragi’s idea of an “integrated whole” should not be this kind of entertaining harmoniousness. Yes, what the composition of this “Art of the Heisei Period” lacks, is boringness. And after all, weren’t the Heisei years dreadfully “boring”?

Chim↑Pom: Installation view (Photo: Kioku Keizo)

Suddenly, the view spreads out before us. Haibara Chiaki, Ri Jong Ok Drawing for “A Bridge Striding over a Fence” 2015

Artificial Intelligence Art and Aesthetics Research Group: Installation view of What If AI Composed for Mr. S? (Photo: Kioku Keizo)

DIVINA COMMEDIA (the council of divina commedia): Installation view (Photo: Kioku Keizo)

Amid this, Complesso Plastico and Parplume retained a brilliant boringness, stopping people in their tracks in what was otherwise a largely seamless flow of traffic around the venue. These were my favorite exhibits. Privileging the display of young male nudes, they summed up the impact of events during this era, in the case of Complesso Plastico the bubble economy, and Parplume the recession, laying them bare in audacious installations in which the cross-generational similarity of raising meaningless yet oddly confident, unfocused messages overhead like “NEW” (CP) and “Paanyaa” (Parplume) mysteriously managed to animate the exhibition (in a simple fashion).

Complesso Plastico《C+P 2020》, 2020, Installation view (Photo: Kioku Keizo)

Parplume: Installation view (Photo: Kioku Keizo)

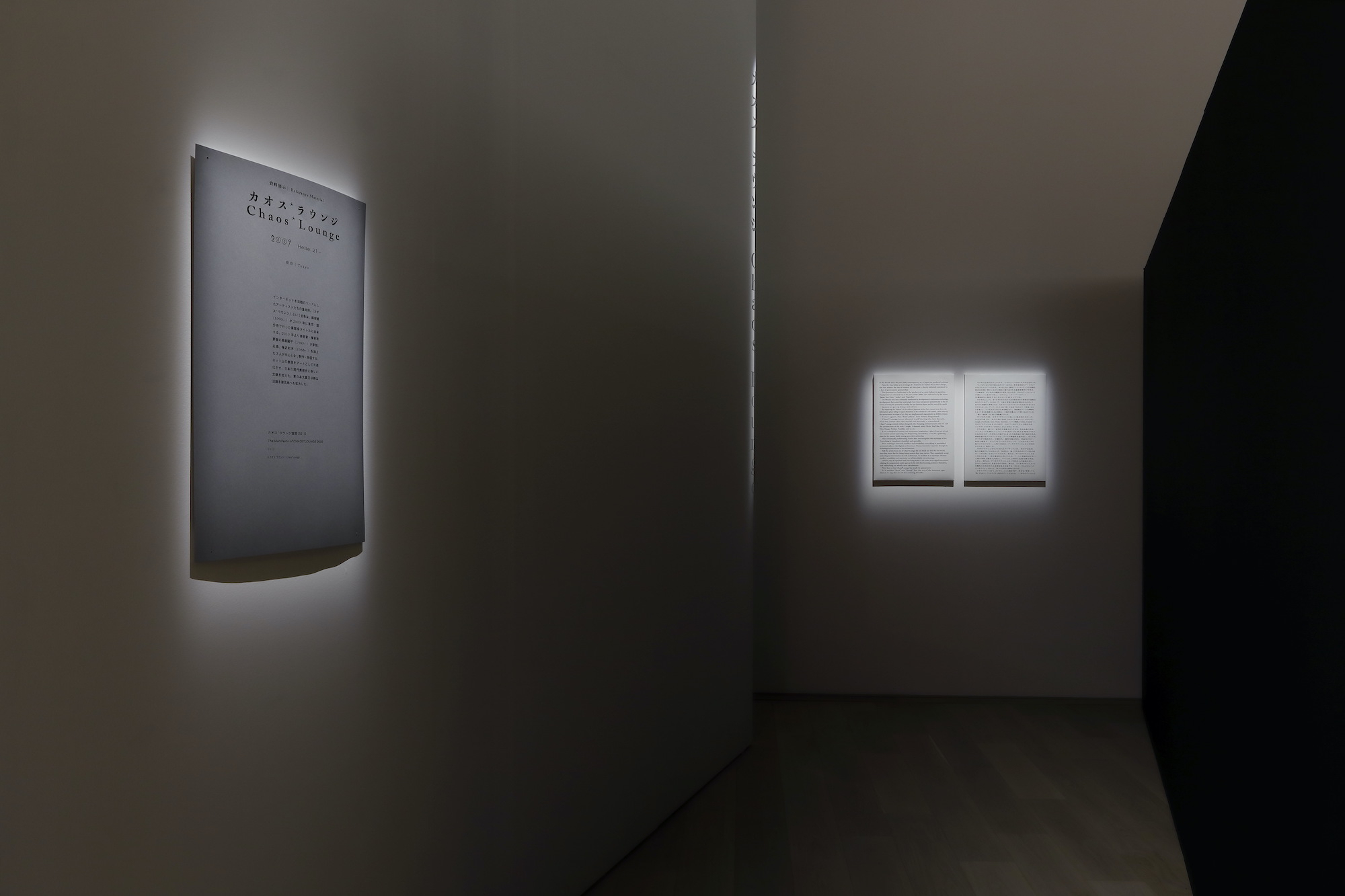

Physically halting the flow of visitors was the Chaos*Lounge display of materials: quite literally because their space resembled a cul-de-sac. In its theatrical unfolding, and rebelling against the institutional art world, the offering by Chaos*Lounge in my view had something in common with TECHNOCRAT (the segment of TECHNOCRAT/Ameya Norimizu’s 1991 solo piece Japanese Songs played here was a masterful effort in which speech collected by phone lines escaped audibly and continuously from the receiver of an old-style black dial telephone, to a jaunty beat, and is connected directly to Chaos*Lounge), but on this occasion it was TECHNOCRAT who created a chaotic lounge.

Chaos*Lounge: Installation view (Photo: Kioku Keizo)

TECHNOCRAT: Installation view (Photo: Kioku Keizo)

In the exhibition handout containing notes on all the works, the museum had excused itself by saying, “Originally we had planned an exhibit covering the activities of Chaos*Lounge around the time of the Tohoku quake. However internal issues for Chaos*Lounge made this difficult, so here we present instead ‘Chaos*Lounge Declaration 2010′ as material.” But really, this is not on. Simply not good enough! If you’re going to call something a display of materials, then for goodness’ sake think of the punters and actually put together a proper display. Sawaragi’s team should have taken their cue from Chaos*Lounge and bombarded us with information, guerilla-fashion, and with acrobatic agility. Even if this “materials display” is significant for being the hard-won product of some tough negotiations, it is out of character for Sawaragi Noi, in my opinion, because it lacks ideas. And material, even. Come on guys, you can do better than make such a “bad place” yourselves!

In saying that, “Bubbles / Debris: Art of the Heisei Period 1989–2019” will not be touring, even in Japan. This is the only place to see it. There are only a few days left, so don’t be content with just the catalog, get along and see it.

Note:

I wrote at the end here, “Don’t be content with just the catalog,” but actually Matsumoto Gento’s book design is brilliant. It ignores the conventional old catalog format, while retaining the heft of a real book. I wish I’d thought of that “disappearing cover” trick. Genius.

Exhibition catalogue (Editors: Mizuno Yoshimi, Mochizuki Koji; Art director/designer: Matsumoto Gento)

Fukunaga Shin (Novelist. Studied at Kyoto University of Art and Design.)