Review

Obstructing light–Takano Ryudai “Daily Photographs 1999–2021”

By Shimizu Minoru

All the photos (except where otherwise noted): ©️Ryudai Takano, courtesy of Yumiko Chiba Associates.

To begin with, while I could understand both the intention and the calculation behind his early offerings, typified by In My Room (2005) and How to Contact a Man (2009), they were of little interest, because although their theme seemed to be that of male sex and sexuality, I failed to find in them anything either specifically “gay” or “erotic.” Assuming this to be true, what connection do these two things absent from Takano’s photography have to photography more generally.

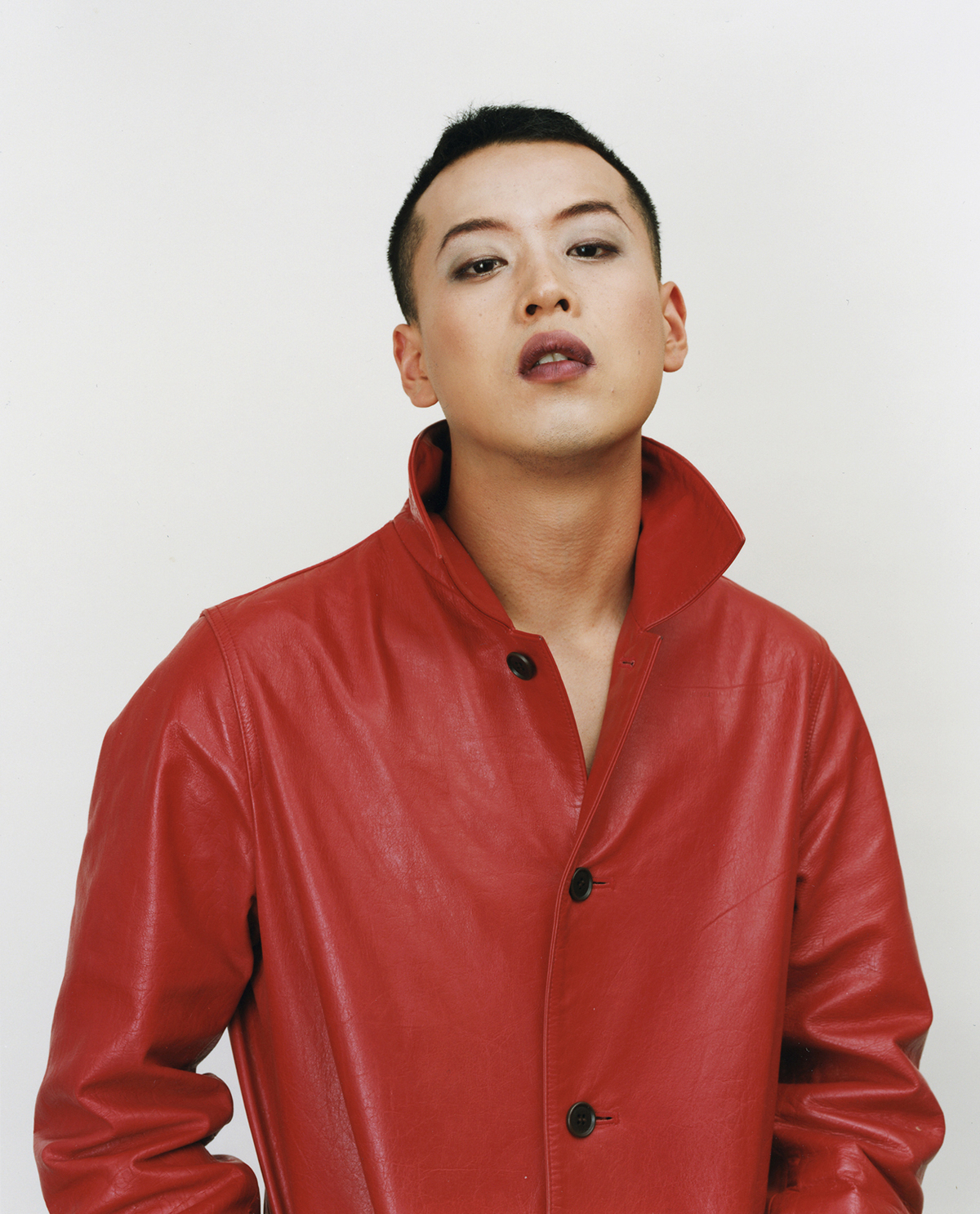

Wearing a red leather coat from the ‘In My Room’ series, 2002.

In the best “gay” art this exquisite balancing act of “off-centeredness” is always evident. Think of the work of Wilhelm von Gloeden, Minor White, Duane Michals, or George Platt Lynes: delicate, vulnerable, occasionally almost cringeworthy in the transparency of its desire. Conversely, what makes much so-called erotic art (Tom of Finland, Tagame Gengoro), and the masculine beauty of male nudes (Bruce Weber, Herb Ritts) so banal is their jettisoning of that balance. Eros will remain elusive as long as one aims for the heart of desire purely by pursuing muscle and pretty boys.

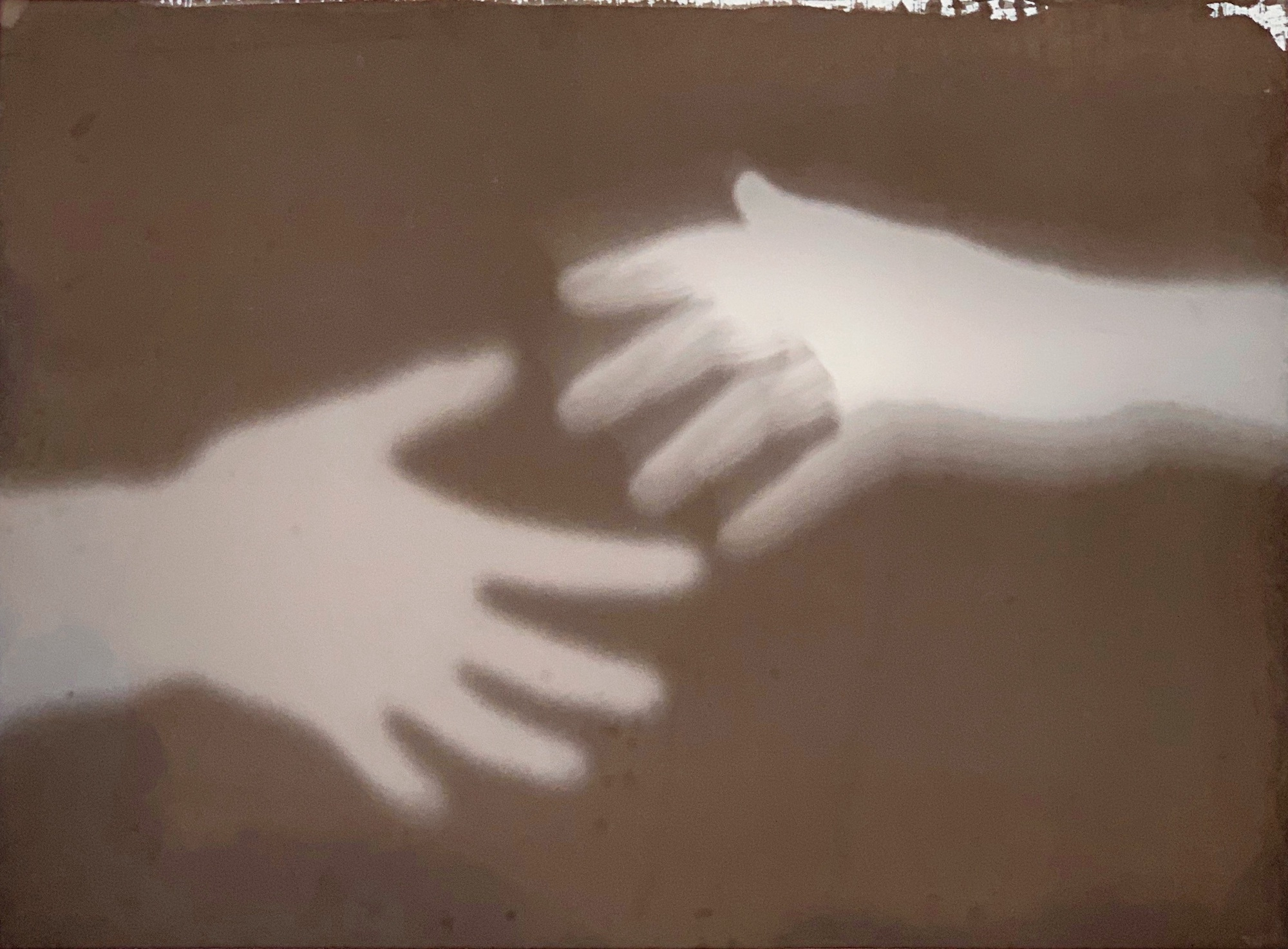

Moreover, this centrifugal force peculiar to gay-style eroticism also manifests as a force leaping from one object to the next, different one, via superficial sensation.

Mario’s voice was large and thick like his hands—except that it carried no sparkle. It struck Querelle slap in the face. It was a brutal, callous voice, like a big shovel.*2

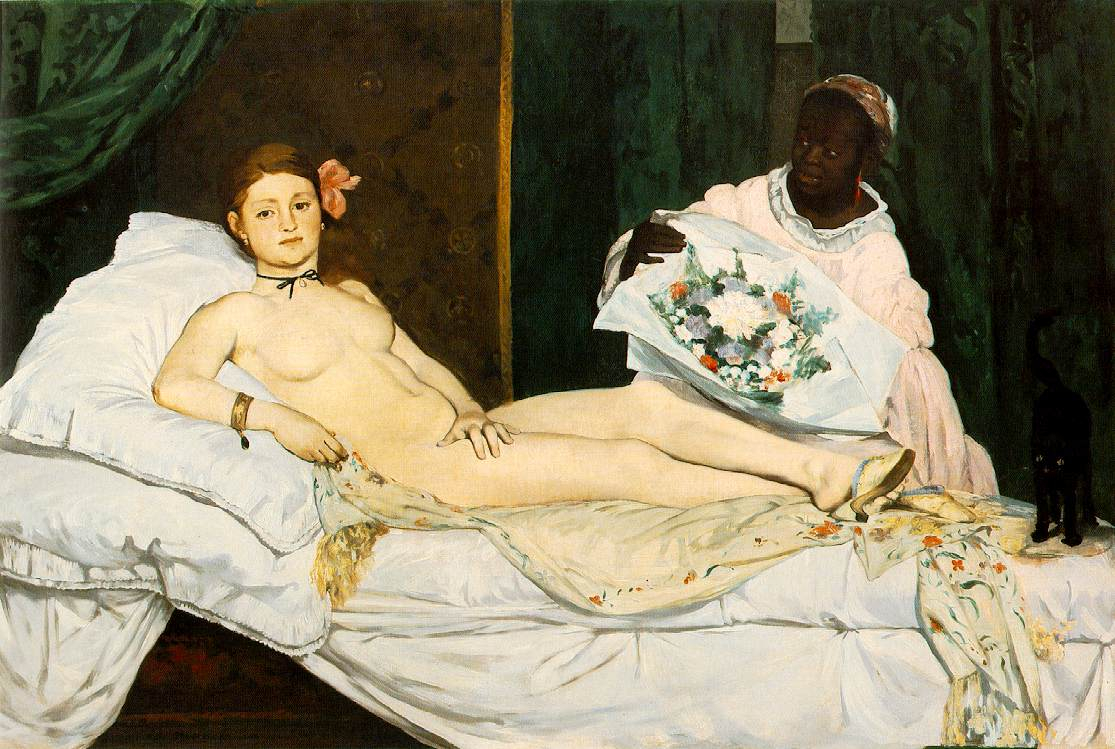

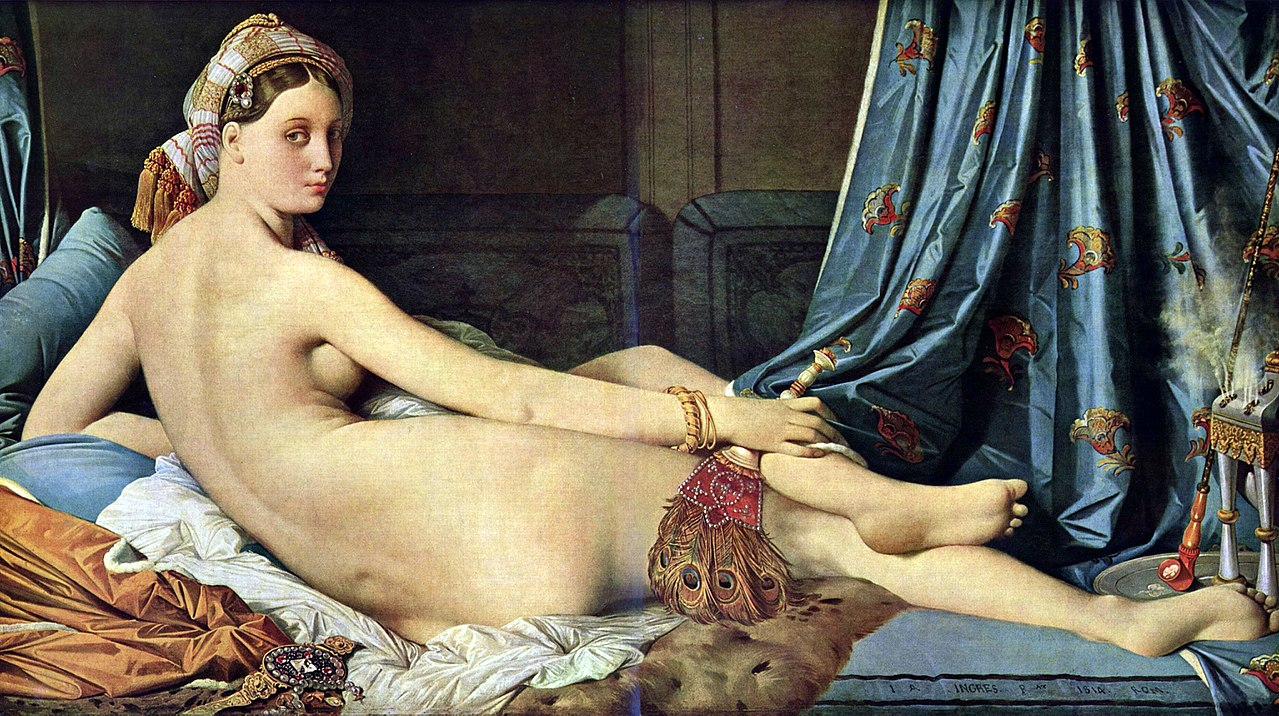

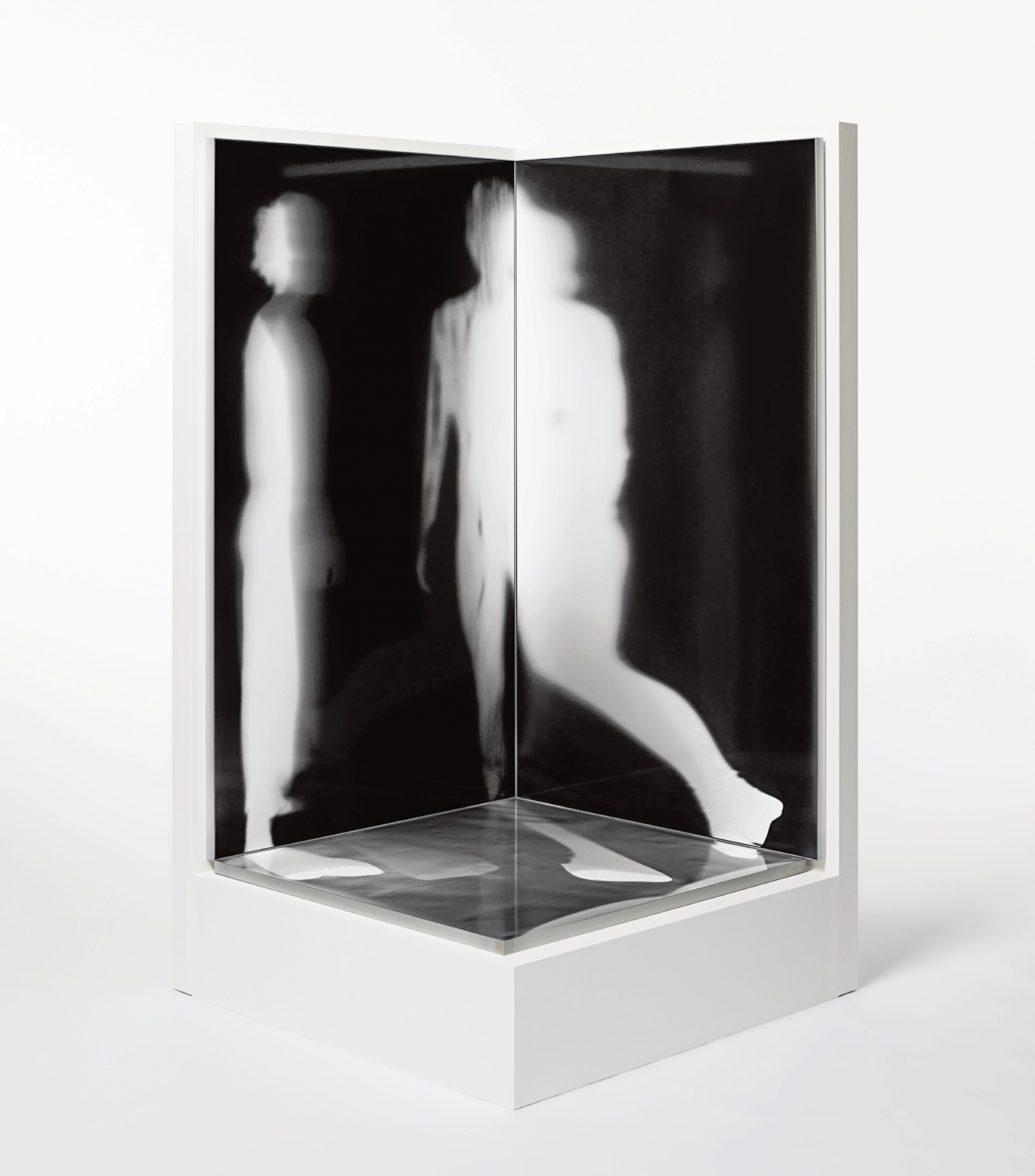

Here is that leap, in this case from brutal voice (hearing) to calloused, beefy hand (touch). For example, when we refer to Herbert Tobias, Robert Mapplethorpe and Wolfgang Tillmans as gay photographers, the core characteristic of their expression is this centrifugal force that jumps from subject to subject, with a certain superficial textural quality acting as an “equal” sign between.Off-centered balance, or leap occasioned by surface eroticism: the name of Takano Ryudai will probably never be listed alongside those above. Takano’s theme is the politics around gender, so fundamentally, his subjects are offered up as identity politics specimens, meaning that their poses—contrapposto, lips slightly parted, odalisque, Olympia—are never anything but standard. Meaning also, on the other hand, that in those works of his not in a “gender” vein, possessing no appropriated formality, there is nothing of obvious interest either technically, or aesthetically.

Kikuo (1999.09.17.Lbw.#11) from the ‘Reclining Woo-Man’ series, 1999.

Édouard Manet, Olympia, 1863. (Source unknown)

Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, Grande Odalisque, 1814. (wartburg.edu)

2003.01.21.#17 from the ‘kasubaba’ series, 2003.

2006.03.06.#b04 from the ‘kasubaba’ series, 2006.

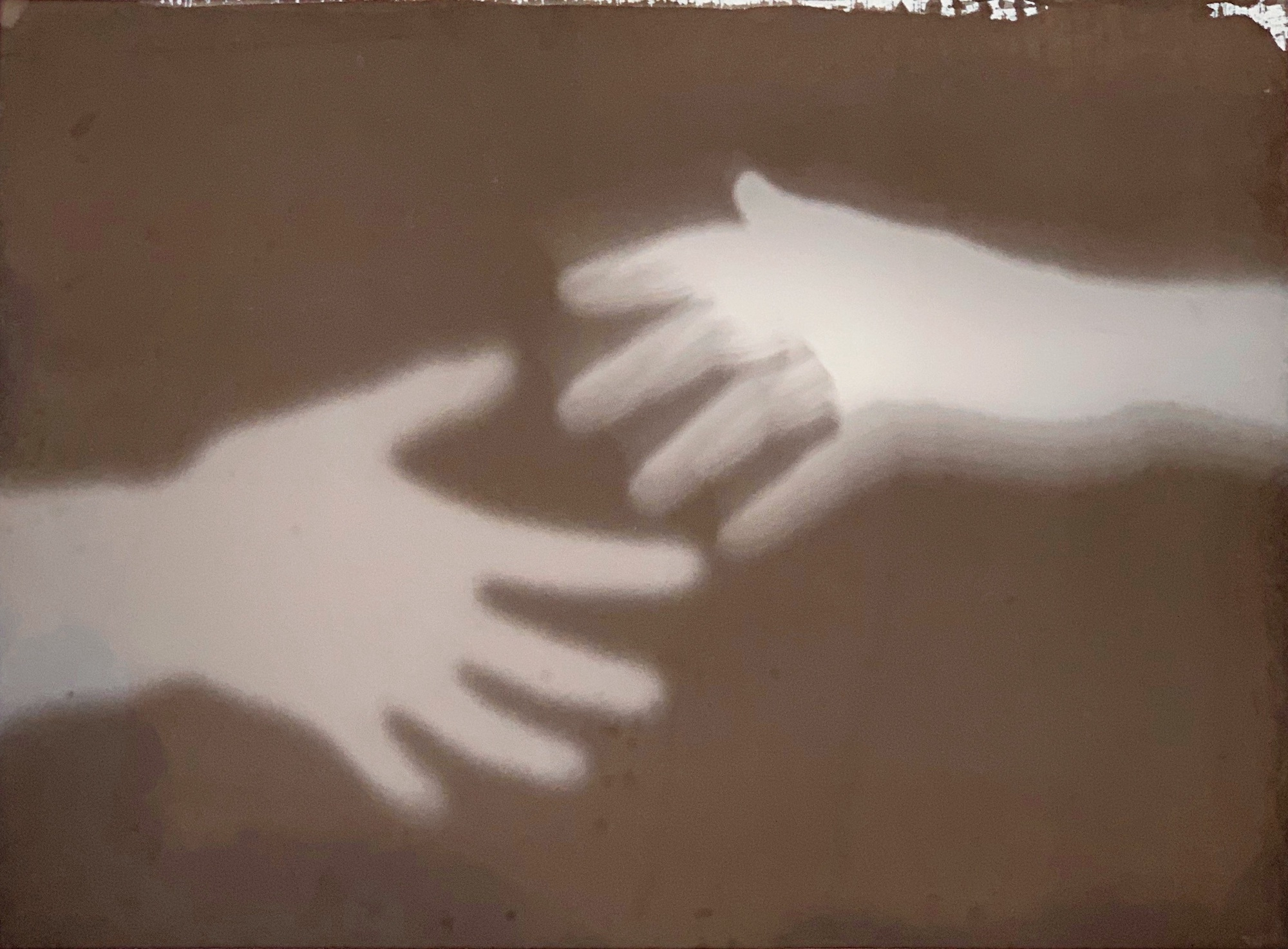

2011.11.25.bw.#a27 from the ‘Photo-Graph’ series, 2011.

2012.03.14.#a26 from ‘Daily Snapshots,’ 2012.

2013.12.04.#a37 from ‘Daily Snapshots,’ 2013.

2014.03.24.#b25 from ‘Daily Snapshots,’ 2014.

2015.04.06.bw#36, 2015.

2016.01.29.#b18 from ‘Daily Snapshots,’ 2016.

2019.12.29.P.#02(Time and Distance) from ‘Red Room Project,’ 2019.

What Kasubaba explored was the removal of subject, viewpoint and focal point. One could say that by doing this, the photographer stepped outside the photograph as a “dioptric” plane. By his shadow series, Takano’s work had already lost any distinction between top and bottom, left and right. The world is none other than a camera/room with a giant aperture, suffused with an image of gigantic blurry light. For Takano, photography is about a single entity casting a shadow there. In the shaded part, images of the world cannot be seen. One could in fact say that this is the “subject” in Takano Ryudai’s photographs. A photographer is someone who obstructs light, and casts shadows on the world.

2021.04.11.Ps.#03 from ‘Sun Light Project,’ 2021.

A modified citation; the original reads: “The foreshortening preferred by the symbol when borne by that which it signifies gives and destroys the signification and the thing signified.”

*2 Jean Genet, Querelle, trans. Anselm Hollo (New York: Grove Press, 1974), 29.

*3 For further information, see Shimizu Minoru, “Analysis of Kasubaba: Variations on the themes of absorption and theatricality,” in Takano Ryudai, Kasubaba (Hiroshima: Daiwa Press, 2011).

*4 Roland Barthes, “Diderot. Brecht, Eisenstein,” in Image Music Text, essays selected and trans. Stephen Heath (London: Fontana Press, 1977), 69–70.

Shimizu Minoru

Critic. Professor, Doshisha University.

※Takano Ryudai “Daily Photographs 1999–2021” is being held at the National Museum of Art, Osaka through September 23, 2021.