Opinion

The Kyoto bankruptcy crisis and the arts

By Ozaki Tetsuya

2021.11.02

Those of you unaware may be surprised to know that the city of Kyoto is on the brink of financial ruin. Yes, Japan’s venerable former capital is currently in hock to the tune of around 850 billion yen. Starting this year (FY2021) Kyoto is expected to post annual financial shortfalls of over 50 billion yen, and if this continues, within ten years may be reduced to the status of a zaisei-saisei dantai: an insolvent municipality forced to undertake financial reforms. In corporate terms this means going bankrupt, the city of Yubari in Hokkaido being the only prior Japanese local authority to achieve this dubious honor, in 2010.

The problem is a structural one that predates the pandemic plunge in tourist numbers, with one cause said to be the large public works projects, such as new subway line construction, undertaken during the bubble years. Some reports say that the city authorities’ eagerness to attract hotels has pushed housing prices through the roof, driving those with young families outside the city limits and thus reducing revenue from resident tax. Undeniably there have been some obvious errors in governance, including over-optimistic forecasting, and liquidation of the “Public Sinking Fund” to make up for losses, but I shall refrain here from blaming the mayor, or the city government.

As a lover of art and the performing arts, my main concern lies rather with what will happen to the arts and culture budget. Funding from the sources like the Agency for Cultural Affairs tends to be on a “half-subsidy” basis, with the city having to match the funds granted by the government agency. Which means that if money from the city is reduced say by two million yen from ten to eight, the scale of the project in question will be reduced from 20 million to sixteen, that is, shrink by four million yen. Which means fewer or different projects being chosen. Event organizers will be hit hard.

In a situation like this there will be the inevitable calls from various quarters for the arts to “pay their own way.” Which means increase the number of programs with mass appeal that will attract the crowds, and run art fairs and auctions to raise cash independently. Even artists need to eat, after all, and it is up to individuals whether they put their work up for sale. However, public facilities and educational institutions as a rule run on a non-profit basis, and if they become involved in trading artworks would be complicit in letting the market reign supreme, with the following negative consequences:

1: Artists will tend to produce works they know will sell, leading to a retreat in experimentation and innovation.

2: A gulf will appear between artists whose work sells and artists whose doesn’t.

3: A risk of separation/estrangement of wealthy and ordinary art lovers.

4: Would be detrimental to the image of public museums, increasing negative misconceptions of contemporary art.

1 and 2 mean, for example, the possibility of only two-dimensional works or small objects easy to display indoors being promoted and celebrated, and artists avoiding the likes of installations and research-based artworks. One is reminded of an unfortunate precedent for this: Michel Tapié recommending tableaux because such works were “portable and easy to sell,” thus changing the style of the Gutai artists overnight. 3 is not hard to envisage in today’s crazy art market. The “misconceptions” in 4 refers to contemporary art – ambiguous, intellectual art that requires “reading” – being mistaken for simple, sensory, visual entertainment. All in all, throwing art back to its position of a hundred years ago.

For example, Gisèle Vienne and Etienne Bideau-Rey’s “Showroomdummies #4” produced as part of the repertory at the ROHM Theatre in FY2019 was invited to take part in Le Festival d’Automne à Paris, a top international performing arts festival. The pandemic put a stop to this, but thanks in part to crowdfunding, it is now, rather wonderfully, to be performed in Paris.

For example, Gisèle Vienne and Etienne Bideau-Rey’s “Showroomdummies #4” produced as part of the repertory at the ROHM Theatre in FY2019 was invited to take part in Le Festival d’Automne à Paris, a top international performing arts festival. The pandemic put a stop to this, but thanks in part to crowdfunding, it is now, rather wonderfully, to be performed in Paris.

Or take “Dialogues with the Collection: 6 Rooms,” which opened at the Kyoto City KYOCERA Museum of Art on October 9, for which artists, sculptors etc with a Kyoto connection such as Miyanaga Aiko and Takahashi Kohei have selected a number of works from the museum’s collection to present alongside their own offerings. Here is a show that gives a real sense, from “dialogue” between present and past, of history and tradition being passed down to the next generation (to 12/5). “Modern Architecture in Kyoto” running almost concurrently is also exactly what it says on the label: a well-designed show that opens up an interesting circuit around the streets of Kyoto where the buildings still remain (to 12/26). Holding more and more brilliant exhibitions like these, will help the eyes and ears of the locals to become more discerning, enhance the capabilities of local artists, and the museums’ international profile, and add substantively to the city’s attractiveness as a cultural center.

Or take “Dialogues with the Collection: 6 Rooms,” which opened at the Kyoto City KYOCERA Museum of Art on October 9, for which artists, sculptors etc with a Kyoto connection such as Miyanaga Aiko and Takahashi Kohei have selected a number of works from the museum’s collection to present alongside their own offerings. Here is a show that gives a real sense, from “dialogue” between present and past, of history and tradition being passed down to the next generation (to 12/5). “Modern Architecture in Kyoto” running almost concurrently is also exactly what it says on the label: a well-designed show that opens up an interesting circuit around the streets of Kyoto where the buildings still remain (to 12/26). Holding more and more brilliant exhibitions like these, will help the eyes and ears of the locals to become more discerning, enhance the capabilities of local artists, and the museums’ international profile, and add substantively to the city’s attractiveness as a cultural center.

In October 1978, Kyoto unveiled its “Declaration of Kyoto as a City Open to the Free Exchange of World Cultures,” stating, “We must communicate widely with the world, and through international exchanges Kyoto must be always renewed culturally and continue to create her own unique culture. It is our hope, therefore, to make Kyoto a center of international cultural exchange.” To my mind, this was a pioneering declaration that demonstrated the city’s readiness to help lead global culture in a manner on a par with centers like Paris and New York. Once the pandemic subsides to some extent, the world will open up again, and when it does cultural tourism will flourish and serve as a major source of revenue particularly for countries like Japan.

In October 1978, Kyoto unveiled its “Declaration of Kyoto as a City Open to the Free Exchange of World Cultures,” stating, “We must communicate widely with the world, and through international exchanges Kyoto must be always renewed culturally and continue to create her own unique culture. It is our hope, therefore, to make Kyoto a center of international cultural exchange.” To my mind, this was a pioneering declaration that demonstrated the city’s readiness to help lead global culture in a manner on a par with centers like Paris and New York. Once the pandemic subsides to some extent, the world will open up again, and when it does cultural tourism will flourish and serve as a major source of revenue particularly for countries like Japan.

What concerns me here is the presence of temples that charge admission, but are basically untaxed. In the 1980s, when the city’s finances were under similar pressure to now, the Kyoto municipal authorities and Kyoto Buddhist Organization clashed over what was known as the Kyoto Old Capital Preservation Cooperation Tax (Old Capital Tax). The KBO’s strongarm tactic of closing temples to visitors won the day, the city abandoned plans for the tax, and the subject of an Old Capital Tax has been taboo ever since. The KBO’s assertion that visiting temples is a religious act, and they would therefore not allow worshippers to be taxed, is pure sophistry, but the authorities’ attempt to bulldoze through the tax undoubtedly did aggravate the dispute.

Temples and shrines are quintessential Kyoto, and ways must be found to retain them. Many of the buildings are old, and expensive to preserve and renovate. In saying this, paying an appropriate amount of tax at a time of crisis like this, to help the city return to better financial health, is surely in line with current public sentiment both in Kyoto and the rest of the country.

A proportion of temples are proactive in their support of the arts and culture. Surely there must be some policy by which everyone wins: temples, those in the arts, local residents, and the authorities. I very much hope that the public, private and religious sectors can come up with some way of working together to preserve, or rather further enhance, the allure of Japan’s old capital.

Ozaki Tetsuya

Journalist/art producer. Editor-in-chief, Realkyoto Forum (ICA Kyoto)

The problem is a structural one that predates the pandemic plunge in tourist numbers, with one cause said to be the large public works projects, such as new subway line construction, undertaken during the bubble years. Some reports say that the city authorities’ eagerness to attract hotels has pushed housing prices through the roof, driving those with young families outside the city limits and thus reducing revenue from resident tax. Undeniably there have been some obvious errors in governance, including over-optimistic forecasting, and liquidation of the “Public Sinking Fund” to make up for losses, but I shall refrain here from blaming the mayor, or the city government.

As a lover of art and the performing arts, my main concern lies rather with what will happen to the arts and culture budget. Funding from the sources like the Agency for Cultural Affairs tends to be on a “half-subsidy” basis, with the city having to match the funds granted by the government agency. Which means that if money from the city is reduced say by two million yen from ten to eight, the scale of the project in question will be reduced from 20 million to sixteen, that is, shrink by four million yen. Which means fewer or different projects being chosen. Event organizers will be hit hard.

In a situation like this there will be the inevitable calls from various quarters for the arts to “pay their own way.” Which means increase the number of programs with mass appeal that will attract the crowds, and run art fairs and auctions to raise cash independently. Even artists need to eat, after all, and it is up to individuals whether they put their work up for sale. However, public facilities and educational institutions as a rule run on a non-profit basis, and if they become involved in trading artworks would be complicit in letting the market reign supreme, with the following negative consequences:

1: Artists will tend to produce works they know will sell, leading to a retreat in experimentation and innovation.

2: A gulf will appear between artists whose work sells and artists whose doesn’t.

3: A risk of separation/estrangement of wealthy and ordinary art lovers.

4: Would be detrimental to the image of public museums, increasing negative misconceptions of contemporary art.

1 and 2 mean, for example, the possibility of only two-dimensional works or small objects easy to display indoors being promoted and celebrated, and artists avoiding the likes of installations and research-based artworks. One is reminded of an unfortunate precedent for this: Michel Tapié recommending tableaux because such works were “portable and easy to sell,” thus changing the style of the Gutai artists overnight. 3 is not hard to envisage in today’s crazy art market. The “misconceptions” in 4 refers to contemporary art – ambiguous, intellectual art that requires “reading” – being mistaken for simple, sensory, visual entertainment. All in all, throwing art back to its position of a hundred years ago.

*

In the plan for Kyoto’s administrative and financial reform adopted in August this year, the section outlining strategies to enable the city to grow and evolve lists as one policy that of “Creating a favorable culture-and-economy cycle.” If this strategy is to be employed, rather than being cut the arts and culture budget surely ought to be increased. Institutions and events with which the city is directly involved, such as the Kyoto Art Center, Kyoto City KYOCERA Museum of Art, ROHM Theatre Kyoto, and Kyoto International Performing Arts Festival (Kyoto Experiment), do after all for the most part make use of Kyoto’s human and cultural assets and progressive qualities in highly original events and programs that contribute to the city’s brand.

Kyoto City KYOCERA Museum of Art

ROHM Theatre Kyoto

Scene from Gisèle Vienne and Etienne Bideau-Rey’s “Showroomdummies #4”

ROHM Theatre Kyoto, 2020. ⓒYuki Moriya

Image used for the crowdfunding. ⓒYuki Moriya

Miyanaga Aiko’s dialogue, “Tracing Time”(2021), involves ceramics from the Meiji to Showa periods fired in her family’s Tozan Kiln.

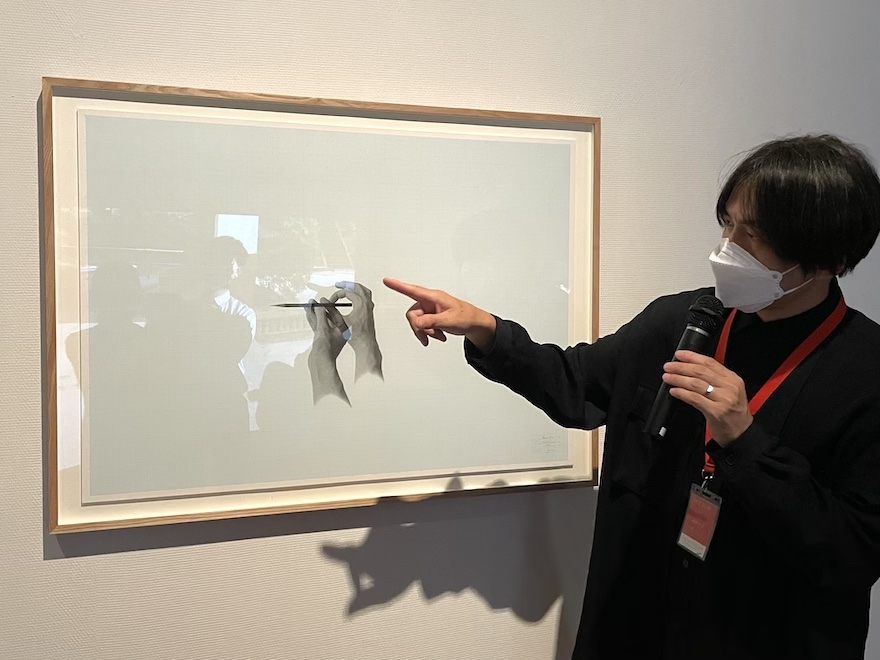

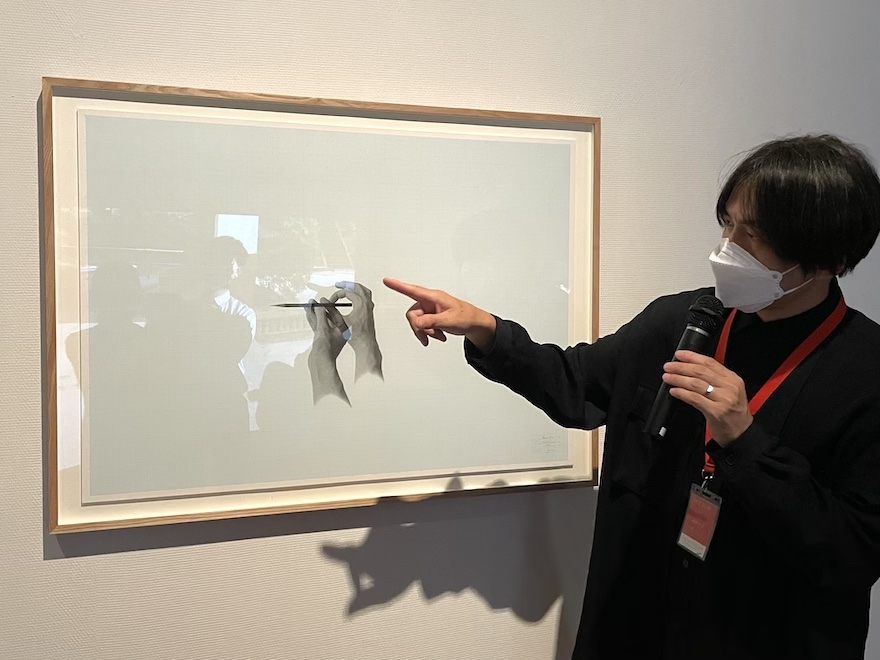

Takahashi Kohei’s dialogue, “Ikei no katachi, aruiha kanki no furumai (Forms of awe, or actions of evocation)”(2021), embraces the work of artist forefathers Ida Shoichi and Kimura Hideki.

Takahashi giving commentary on Kimura’s “Pencil 2-3″(1974).

Installation view of “Modern Architecture in Kyoto”. Maquettes of Fujii Koji’s “Chochikukyo” and chairs designed by Fujii.

What concerns me here is the presence of temples that charge admission, but are basically untaxed. In the 1980s, when the city’s finances were under similar pressure to now, the Kyoto municipal authorities and Kyoto Buddhist Organization clashed over what was known as the Kyoto Old Capital Preservation Cooperation Tax (Old Capital Tax). The KBO’s strongarm tactic of closing temples to visitors won the day, the city abandoned plans for the tax, and the subject of an Old Capital Tax has been taboo ever since. The KBO’s assertion that visiting temples is a religious act, and they would therefore not allow worshippers to be taxed, is pure sophistry, but the authorities’ attempt to bulldoze through the tax undoubtedly did aggravate the dispute.

Temples and shrines are quintessential Kyoto, and ways must be found to retain them. Many of the buildings are old, and expensive to preserve and renovate. In saying this, paying an appropriate amount of tax at a time of crisis like this, to help the city return to better financial health, is surely in line with current public sentiment both in Kyoto and the rest of the country.

A proportion of temples are proactive in their support of the arts and culture. Surely there must be some policy by which everyone wins: temples, those in the arts, local residents, and the authorities. I very much hope that the public, private and religious sectors can come up with some way of working together to preserve, or rather further enhance, the allure of Japan’s old capital.

Ozaki Tetsuya

Journalist/art producer. Editor-in-chief, Realkyoto Forum (ICA Kyoto)