Op-ed column

Conflict in the public realm

By Azby Brown

The reaction from artists and cultural professionals upon hearing about the removal plan was one of great alarm. Novelist Fukunaga Shin learned of the plans to demolish the work and published a report widely circulated online that questioned the decision making process. Subsequent newspaper reports led to widespread discussion, public outcry from prominent critics and curators, and an online signature drive. On January 19, Takashimaya announced that it had shelved its demolition plan. The artist feels that the speed and understanding with which the company handled the situation is commendable. This is a good outcome.

Although this particular issue seems to have been resolved, the entire episode has laid bare a number of extremely concerning realities regarding the insecure status of public artworks in Japan, and the lack of adequate protection for them as shared cultural assets. Perhaps the biggest problem is that the original rationale behind the art-centered development plan for the FARET Tachikawa itself, and the historical background of the area, had been forgotten. History is a continuum, and prior conflicts never really disappear. The problems that formed the context when Mt. Ida was planned and constructed in the early 1990’s are closely related to many that confront the culture and political economy of the world today. These center on defining and protecting the public realm.

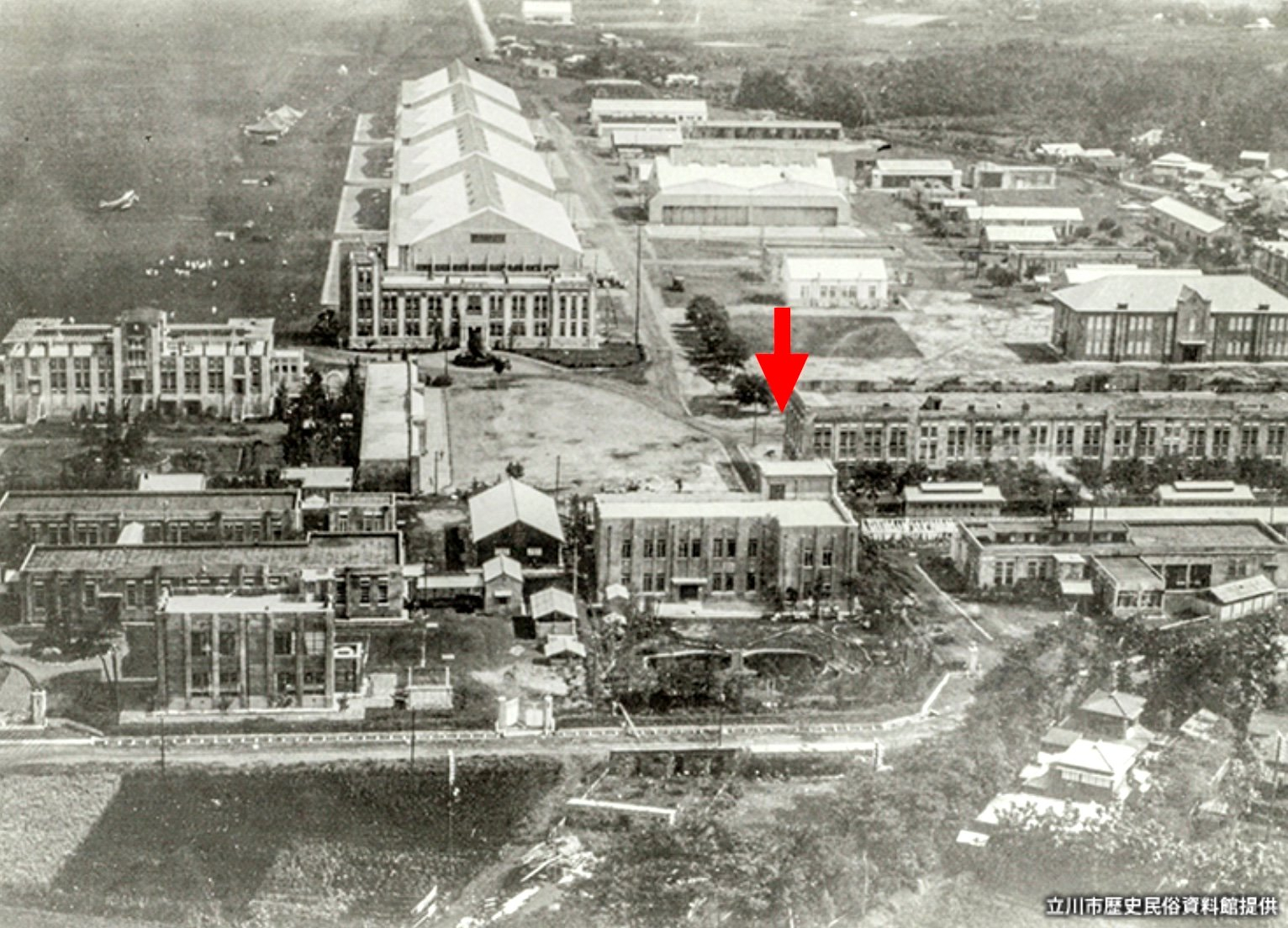

Image from the Taisho period or early Showa period. The four large buildings lined up vertically in the center are hangars, and the building in front of them is the battalion/regiment headquarters.

Mt. Ida location indicated by red arrow. Republished from <https://smtrc.jp/town-archives/city/tachikawa/p04.html>

Despite the specifics of ownership in each case, Mt. Ida and the other artworks at FARET Tachikawa are part of a historic art-centered public urban renewal plan. In cases like this, it should be made explicit from the outset in a binding way that changes which affect the artworks, including their relocation or removal, would require the consent of all those involved, with adequate and transparent prior consultation and advisement by local cultural institutions. This is to be expected as standard practice. The existing agreements and understandings have worked well enough until now, and Mt. Ida was an unusual case which says as much about corporate decision making in Japan as it does about public art. As is now abundantly clear, however, it is not enough to merely expect everyone to do the right thing.

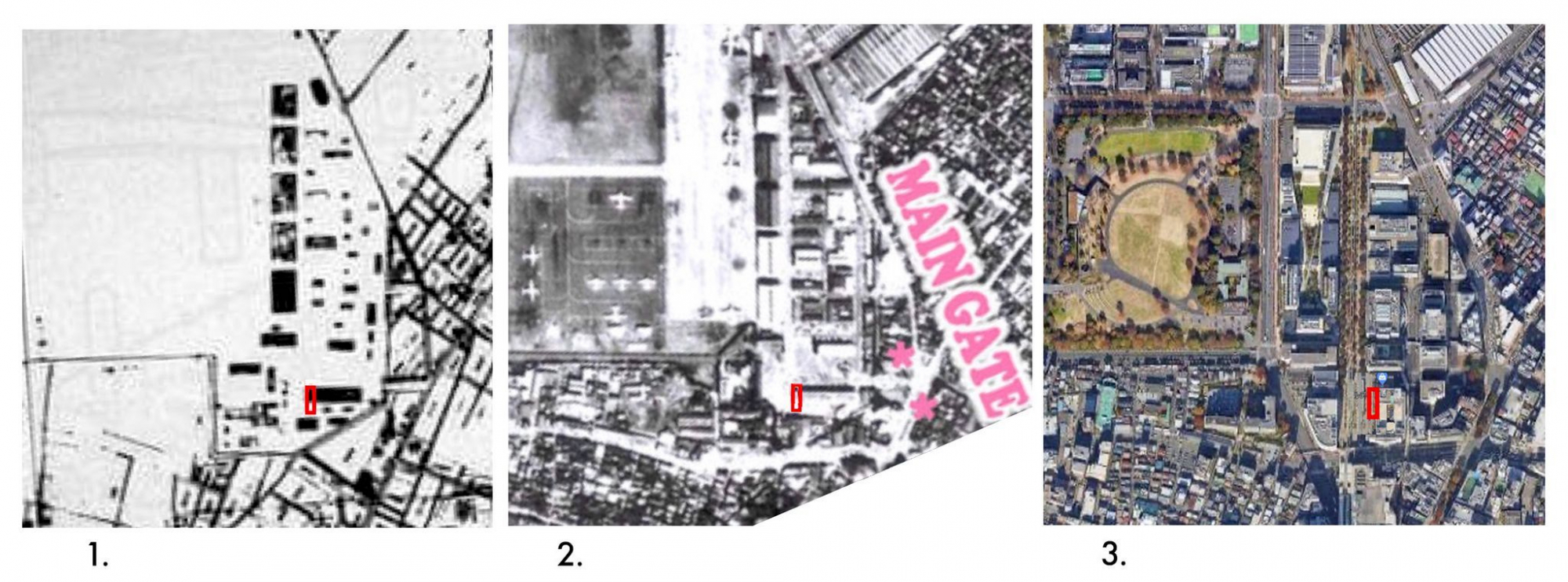

History of Mt. Ida site (artwork location indicated by red outline):

1. Japanese government map, undated. Likely ca. 1940.

2. 1965 aerial photo, with Tachikawa airbase main gate indicated (by Mike Skidmore, ca. 2020).

3. Current satellite image of FARET Tachikawa site, 2022.

Could public artwork encourage us to notice what is relegated to the fringes of our consciousness? This in itself is intellectually quite ambitious within the context of urban planning, then as now. In the case of FARET Tachikawa, however, the most significant presence that has been relegated to the fringes of consciousness is the violent history of the site itself.

Prior to and during the Second World War, the site that is now FARET Tachikawa was occupied by a major Japanese airbase. Land belonging to local farmers had been forcibly requisitioned for its construction. After the war, it became an American airbase, and following the Korean War, the Japanese government again began forcibly requisitioning land on behalf of the American military so that the runway could be extended. Japanese authorities began to fence in the land to be expropriated. A major resistance movement by farmers and citizens known as the Sunagawa Struggle began on the site in May of 1955 and continued for two years, marked by great violence as police viciously beat non-resisting protestors as they sat in groups. The base expansion project was subsequently suspended, and although land inside the despised fence became vacant, farmers continued to cultivate part of it voluntarily.

Local residents protesting during the “Sunagawa Struggle” with a US military transport plane flying overhead.[Image is ca. 1956] Republished from <https://smtrc.jp/town-archives/city/tachikawa/p07.html>

– Okazaki Kenjiro The plans to demolish Mount Ida (the boy Paris is still shepherding)

Not all of the artists who participated in the FARET Tachikawa Art project seem to have understood the “From Function to Fiction” concept or the painful historical context of the site. Although some of the artists from overseas produced excellent work, likely few of them had adequate time onsite to absorb it. As it stands, the sculptures at FARET Tachikawa include some that could be described as “parasitic” on the urban functionality of the city, and others are closer in character to conventional outdoor art objects. But some, like Mt. Ida meet the stated requirements quite well.

Another significant historical vector at play here involves the increasing expectation of impermanence and the implications of that. In recent decades, Japan has seen a proliferation of temporary geijutsusai public art festivals. Large-scale examples are held regularly in many parts of the country, and attract large audiences, who have many opportunities to experience the excitement of participation. Although provocative work can be found, as Okazaki has pointed out, the format is “scrap and build” art, and the excitement and significance of the temporary work dissipates when it is dismantled at the end of the festival. (It’s worth noting that Art Front Gallery, which planned FARET Tachikawa, pioneered this kind of festival in Japan and remains very active in the field).

On the one hand, as temporary public festival-style art works become more popular, we’ve become conditioned to expect less from them. To provide momentary fun and diversion is usually enough to fulfill their purpose. More significantly, however, the expectations and intent behind geijutsusai are the direct opposite of what FARET Tachikawa was ostensibly established to do. FARET is supposed to be about placing works where they will remain as permanent presences in the urban environment, to be noticed and regarded by residents and visitors over long periods of time, and to literally shape perceptions of that environment in a fundamental way. Okazaki’s work embodies these expectations admirably, revealing itself slowly as it is noticed by passers-by over the course of repeated encounters. Overall, however, in Japanese society important questions regarding the public domain remain unanswered, and attention is dominated instead by the proliferation of popular consumer culture events.

The lessons of Mt. Ida’s narrow survival must be taken seriously. In a context where the large-scale privatization of public space has become the norm, what is “public” now? Who decides what happens there? At what point do average citizens become legitimate stakeholders in artworks or even buildings and landscapes which have achieved cultural value despite being privately owned? What are the rights of artists then? In the case of large-scale outdoor artworks, some are implicitly protected by their high monetary value. But humans live for intangibles like familiarity and belonging, which equally deserve protection. The threatened destruction of Okazaki’s Mt. Ida, a work which attempted to reverse by sculptural means the history of expropriation on its site and the exclusion of those on the periphery, gives us an important opportunity to reflect on the role site-specific public urban artworks can play, and how much we should expect from them. This is, after all, an artwork which once again fought the battle over land at Tachikawa and won.

Azby Brown

Artist, author, architecture researcher. Has lived in Japan since 1985.

azbybrown.com