Cultural Currency 10: Matsue Taiji’s gazetteerCC and Hamaya Hiroshi’s Landscapes of Japan

Alternatives to “Landscape” (Part 2)

By Shimizu Minoru

2023.03.18

Firstly, from the standpoint of seeing “reality as it is” in “struggle,” there are the documentations of anti-government movements, including the 1960 Anpo struggle (protests over the Japan-US Security Treaty) and the protests at Haneda Airport: Hamada Hiroshi’s Chronicle of Grief and Anger (1960), Kitai Kazuo’s Resistance (1965) and Ogawa Shinsuke’s documentary films The Oppressed Students and Report from Haneda (both 1967). Rather than stemming from the influence of William Klein’s New York (1956), the intense “are-bure-boke” (grainy, blurry, out-of-focus) style visible in these works arose and became established naturally from the situation on the ground in which, amid the violence, photographers had to develop their work in temporary darkrooms while facing intimidation from security police seeking to gather corroborating photographs. In Japan, it became a style that symbolized political resistance.

Secondly, there was the realism that arose as a critique of the impotence of the classic documentaries by the likes of Ogawa who sought to reveal “reality as it is” as before while remaining unaware of the advent of the media society, which in the 1970s formed the discourse known as “landscape theory.” A.K.A. Serial Killer (1975) by Adachi Masao (and others), which was described as a “landscape film”; The Extinction of Landscape (1971) by Matsuda Masao, who was also involved in the production of that film; and the essay by Nakahira Takuma, who was a friend of the above-named pair, “Rebellion Against the Landscape: Fire at the Limits of my Perpetual Gazing . . .” (1970), all contain elements of landscape theory. These were theories of an era in which the system of capital and the state truly came to capture the “exterior” as a driving force and self-perpetuate, with the façade of the society that comprises such a system assuming the title “landscape.” Every landscape throughout Japan was “uniformly sealed-up” by the state=capital.1 Landscape was none other than “the text of state authority,” and so one had to destroy landscape=the state=capital, to criticize landscape. This was an ideology of resistance that challenged one to move outside the “exterior” shut in by landscape, to discover “reality as it is” prior to its manipulation by political authority. Japanese landscape theory shows signs of contemporaneity with Nathan Lyons’ landmark exhibition “Contemporary Photographers Toward a Social Landscape” (1966), but in its rehabilitation of “as it is-ness” and its orientation toward struggles against the postwar Japan-US regime it differed markedly from the latter.

Far from abandoning the modernist belief, in a way Hamaya has rendered it “absolute.” Here, “absolute” means that humans are not required. The “exterior as it is” is established as nature in universal time, which is far removed from human time (history). This photobook was published in both Japanese and English editions. Having taken aerial photographs, Hamaya was no doubt conscious of the fact that after the war, most of Japan’s airspace was reserved for the exclusive use of the US military (Yokota airspace, Iwakuni airspace, Kadena airspace, etc.). In this way, both the Japanese who had chosen a concocted space-time and the Americans who controlled it were erased.

Far from abandoning the modernist belief, in a way Hamaya has rendered it “absolute.” Here, “absolute” means that humans are not required. The “exterior as it is” is established as nature in universal time, which is far removed from human time (history). This photobook was published in both Japanese and English editions. Having taken aerial photographs, Hamaya was no doubt conscious of the fact that after the war, most of Japan’s airspace was reserved for the exclusive use of the US military (Yokota airspace, Iwakuni airspace, Kadena airspace, etc.). In this way, both the Japanese who had chosen a concocted space-time and the Americans who controlled it were erased.

What remained was Japan as pure Earth’s surface unseen by anyone. However, the photographer himself came to a different conclusion. “Now that I have finished editing Landscapes of Japan, what comes to mind is people. Perhaps it is just me, but I sense the presence of people in each photograph in Landscapes of Japan. Looking at nature gave me a new perspective on people.”3

What remained was Japan as pure Earth’s surface unseen by anyone. However, the photographer himself came to a different conclusion. “Now that I have finished editing Landscapes of Japan, what comes to mind is people. Perhaps it is just me, but I sense the presence of people in each photograph in Landscapes of Japan. Looking at nature gave me a new perspective on people.”3

1. Nakahira Takuma, “Fire at the Limits of my Perpetual Gazing…” (1970), repr. in For a Language to Come, trans. Franz K. Prichard (Tokyo: Osiris, 2010), np.

2. From the afterword in Landscapes of Japan (1964), repr. in Century of Photography: Hiroshi Hamaya, 1931–1990, exh. cat. (Tokyo: Tokyo Photographic Art Museum, 1997), 135.

3. Ibid.

—————————————————————-

Shimizu Minoru

Critic. Professor, Doshisha University.

Matsue Taiji’s gazetteerCC is available from Akaaka Art Publishing.

*

Famous for such series as “Snow Country” and “Japan’s Back Coast,” Hamaya Hiroshi (1915–1999) was one of Japan’s most leading photographers and a member of the generation (aged 30 at the time of Japan’s defeat in World War II) that believed that as long as “[t]he train came out of the tunnel” traditional Japan “as it is” would still remain. Hamaya was deeply involved in the 1960 Anpo struggle and, as researchers concerned with Japanese photography of this period will no doubt know, was responsible for Chronicle of Grief and Anger. It is difficult to believe that a photographer who participated in the first nationwide protest movement against the continuation of colonial Japan (the absence of “as it is-ness”) would have been satisfied with the kind of beautiful “projection” that would later be commercialized as “Discover Japan” (1970). As is commonly known, the 1960 Anpo struggle ended in a major victory for the ruling Liberal Democratic Party. After forcing a vote on the bill extending the Japan-US Security Treaty through the National Diet, the cabinet of Prime Minister Kishi resigned and a general election was held, resulting in the LDP gaining an outright majority. The people of Japan chose to live the fiction of a colony. Hamaya lost faith in such Japanese people and moved toward a “Japan” without the Japanese, which is to say the Japanese archipelago absolutely as it is in the form of geographical nature. “My wife was afraid I would become a misanthrope, and I did actually develop a feeling of distrust and alienation from people—an experience that was a first for me. … That was why I avoided anything that hinted of human beings. I was consciously eliminating everything not of the natural world—and I started by rejecting people.”2 He spent the next four years photographing Japan, resulting in Landscapes of Japan (Heibonsha, 1964).

“L. Furen; Deltaic plain”

“Ko-numa; Watasuge (Eriophorum gracile) “

“Choja-ga-mori, Akiyoshi-dai; Sink holes”

“Jizo-yama; Rime on pine forest”

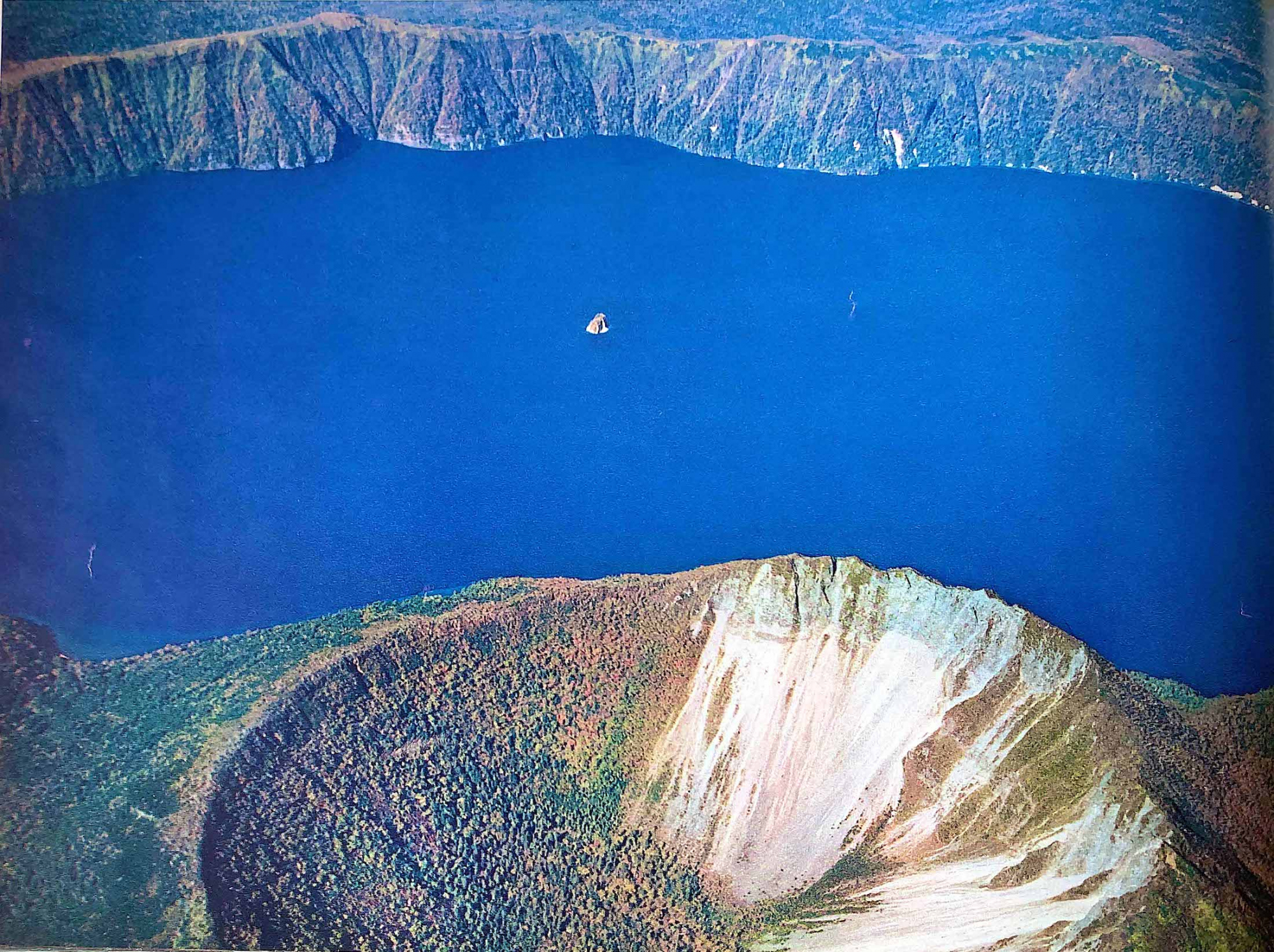

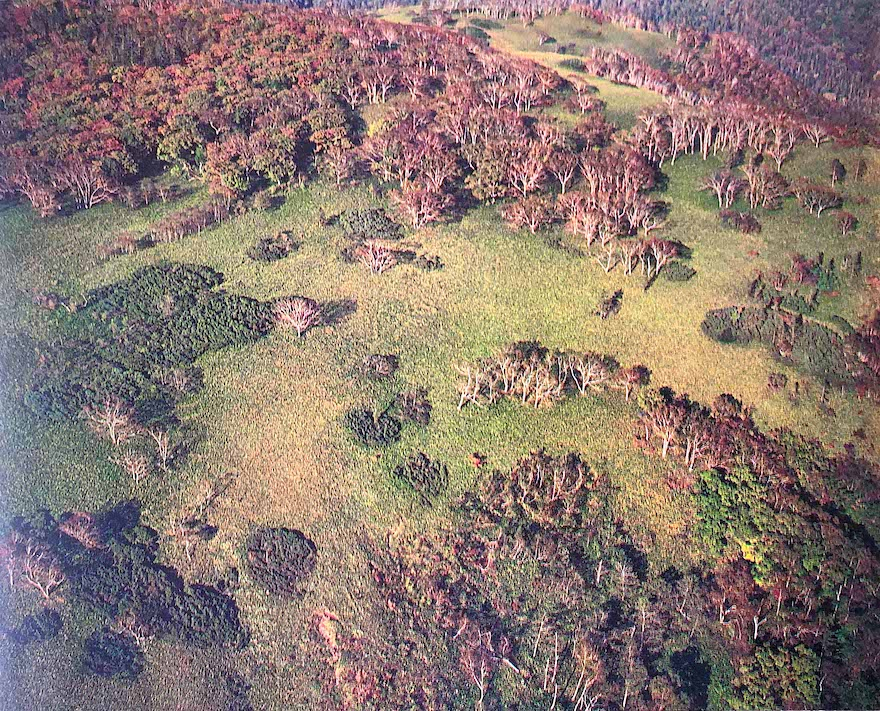

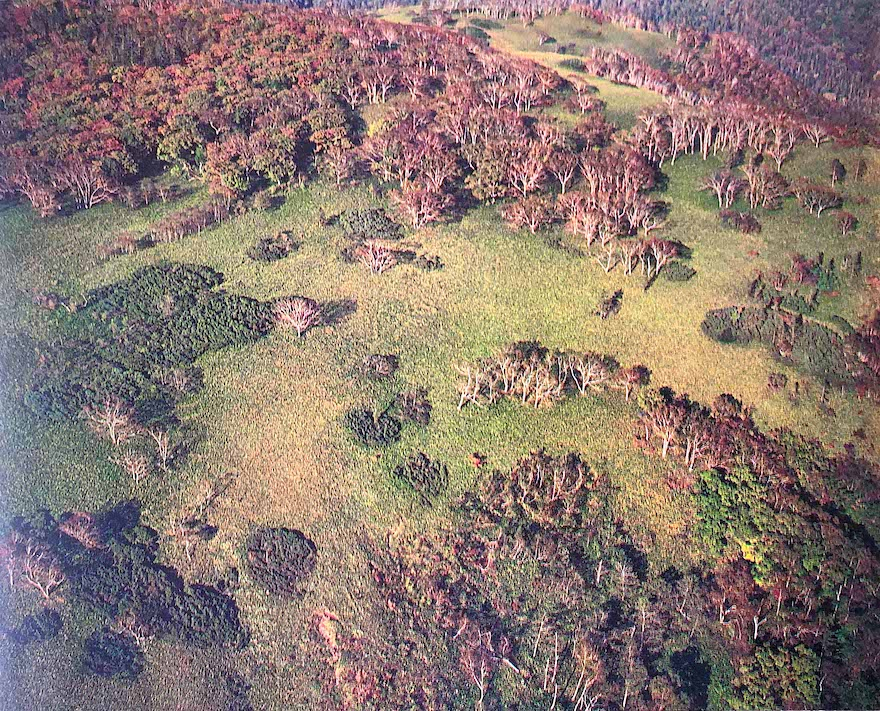

(These and all the images below from Landscapes of Japan. I have purposefully chosen works that more or less conform to the format of Matsue’s photographs—views from above, front lighting, upright, landscape orientation, horizons cut. Because they have been scanned from old photobooks, the colors are somewhat faded compared to the works in the Tokyo Photographic Art Museum retrospective catalogue [1997].)

“Cape Ashizuri; Evergreen woods”

“Mt. Mashu; Mixed forests”

“Mt. Mokoto; Parkland”

“Mt. Daisetsu; Gallery forest”

(To be continued)

—————————————————————-1. Nakahira Takuma, “Fire at the Limits of my Perpetual Gazing…” (1970), repr. in For a Language to Come, trans. Franz K. Prichard (Tokyo: Osiris, 2010), np.

2. From the afterword in Landscapes of Japan (1964), repr. in Century of Photography: Hiroshi Hamaya, 1931–1990, exh. cat. (Tokyo: Tokyo Photographic Art Museum, 1997), 135.

3. Ibid.

—————————————————————-

Shimizu Minoru

Critic. Professor, Doshisha University.

Matsue Taiji’s gazetteerCC is available from Akaaka Art Publishing.