Cultural Currency 23: "Heshiki Kenshichi: Lungs of a Goat"@The Third Gallery Aya

The depth of the sky (part 3)

By Shimizu Minoru

2024.04.15

Let us return to Yagi no hai (Lungs of a Goat).

Firstly, the title is a reference not to the goat of “goat-song” (ie, tragedy1), but to the theory that in goats raised for meat, the lungs are the only internal organs that cannot be eaten.2 Among livestock, goats rank below sheep, cows and pigs as a foodstuff. The things left untouched when the lowest ranked livestock is slaughtered. What is Heshiki Kenshichi using “goats” and “lungs” to represent? It seems certain that he sees in the things that are left behind, however defeated and ruined one may be, a fire that will not go out and cannot be extinguished, or something like the core of existence.3 Perhaps he is suggesting that in Japan, which had become the U.S.’s livestock (Kachikujin Yapū / Yapoo, the Human Cattle4), the thing that could not be digested and was left behind even after Japan’s defeat was Okinawa. Or perhaps the goat (Okinawa), the lowest ranked among the livestock (Japan), was reduced to a set of lungs and left behind (like human bones in a cave) amid the loss of countless lives in the Battle of Okinawa.

Secondly, even if we include Heshiki’s work among konpora photography, its meaning is completely different not only from the original konpora photography (the U.S. artists who took part in the 1966 “Contemporary Photographers” exhibition), but also from mainland Japanese konpora photography (Gocho Shigeo, Sekiguchi Masao, Inakoshi Koichi, Shimotsu Takayuki, Tamura Akihide, Niimura Takao, etc.). In general, the distinguishing features of konpora photography lie in its meta-photographic nature. By this I mean firstly that it is photography concerning various aspects (technical, conceptual, artistic) of photography as a medium, but in mainland Japanese konpora photography, this is also expressed as a critical distance with respect to realist photography conditioned by the aforementioned “national polity.” In mainland Japanese konpora photography, a noticeable orientation towards the U.S. can be seen, but a major reason for this was that “military bases” was a privileged subject of Japanese photography.5 These photographers maintained a distance from the symbolic subjects (Okinawa, military bases, the Stars and Stripes, the Rising Sun flag, Black American servicemen, chewing gum, Coca-Cola, etc.) that had become an overload due to the photographic expression of the previous generation, including the Vivo generation, for example, depicting them with eyes awakened to the “self” and to the “here and now everyday,” which is to say a form in which the focus of the artist’s concern was obscured, something for which they had already been judged and criticized by their contemporaries.6 The everyday scenes at the bases they photographed were also examples of the affluent lifestyles the Japanese at the time yearned for. By depicting U.S. military bases on the basis of this “yearned for lifestyle,” mainland Japanese konpora photographers both nullified the emotional overload of the previous generation and assimilated as everyday the inconsistencies concerning the “national polity” that were the source of this overload. Rather than exposing the hidden “as it is,” the scenery “as it is” that had been accepted both good and bad—the “naturalist photography” for which Domon Ken had criticized Kimura Ihei—took on ambiguity on account of it not giving a sense of the maker’s intentions, preserving viewers in a state of suspended judgment.

Secondly, even if we include Heshiki’s work among konpora photography, its meaning is completely different not only from the original konpora photography (the U.S. artists who took part in the 1966 “Contemporary Photographers” exhibition), but also from mainland Japanese konpora photography (Gocho Shigeo, Sekiguchi Masao, Inakoshi Koichi, Shimotsu Takayuki, Tamura Akihide, Niimura Takao, etc.). In general, the distinguishing features of konpora photography lie in its meta-photographic nature. By this I mean firstly that it is photography concerning various aspects (technical, conceptual, artistic) of photography as a medium, but in mainland Japanese konpora photography, this is also expressed as a critical distance with respect to realist photography conditioned by the aforementioned “national polity.” In mainland Japanese konpora photography, a noticeable orientation towards the U.S. can be seen, but a major reason for this was that “military bases” was a privileged subject of Japanese photography.5 These photographers maintained a distance from the symbolic subjects (Okinawa, military bases, the Stars and Stripes, the Rising Sun flag, Black American servicemen, chewing gum, Coca-Cola, etc.) that had become an overload due to the photographic expression of the previous generation, including the Vivo generation, for example, depicting them with eyes awakened to the “self” and to the “here and now everyday,” which is to say a form in which the focus of the artist’s concern was obscured, something for which they had already been judged and criticized by their contemporaries.6 The everyday scenes at the bases they photographed were also examples of the affluent lifestyles the Japanese at the time yearned for. By depicting U.S. military bases on the basis of this “yearned for lifestyle,” mainland Japanese konpora photographers both nullified the emotional overload of the previous generation and assimilated as everyday the inconsistencies concerning the “national polity” that were the source of this overload. Rather than exposing the hidden “as it is,” the scenery “as it is” that had been accepted both good and bad—the “naturalist photography” for which Domon Ken had criticized Kimura Ihei—took on ambiguity on account of it not giving a sense of the maker’s intentions, preserving viewers in a state of suspended judgment.

As mentioned when I discussed Hamaya Hiroshi in an earlier edition of this column,7 there is another type of mainland Japanese photography from the 1970s and beyond, and that is “the last Modernists” (or “deserted landscapes”) type (Yanagisawa Shin, Watanabe Kanendo, Sugimoto Hiroshi, etc.). In the sense that they represent the first postmodernist photography and the last modernist photography, the mainland konpora photographers and the last modernists stand in opposition to each other, but in the context of Japan, both demonstrate the consummation of the suppression of the trauma of Japan’s defeat. The latter expressed the non-existent “as it is” a void. The former endorsed the inconsistencies around the “national polity” as a dual “as it is,” accepting both good and bad, or in other words making no comment either way.8

As mentioned when I discussed Hamaya Hiroshi in an earlier edition of this column,7 there is another type of mainland Japanese photography from the 1970s and beyond, and that is “the last Modernists” (or “deserted landscapes”) type (Yanagisawa Shin, Watanabe Kanendo, Sugimoto Hiroshi, etc.). In the sense that they represent the first postmodernist photography and the last modernist photography, the mainland konpora photographers and the last modernists stand in opposition to each other, but in the context of Japan, both demonstrate the consummation of the suppression of the trauma of Japan’s defeat. The latter expressed the non-existent “as it is” a void. The former endorsed the inconsistencies around the “national polity” as a dual “as it is,” accepting both good and bad, or in other words making no comment either way.8

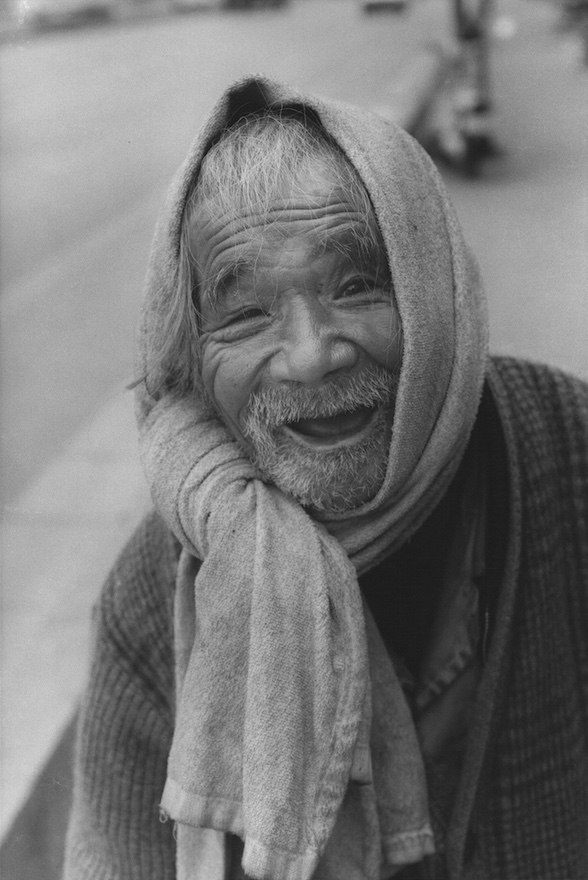

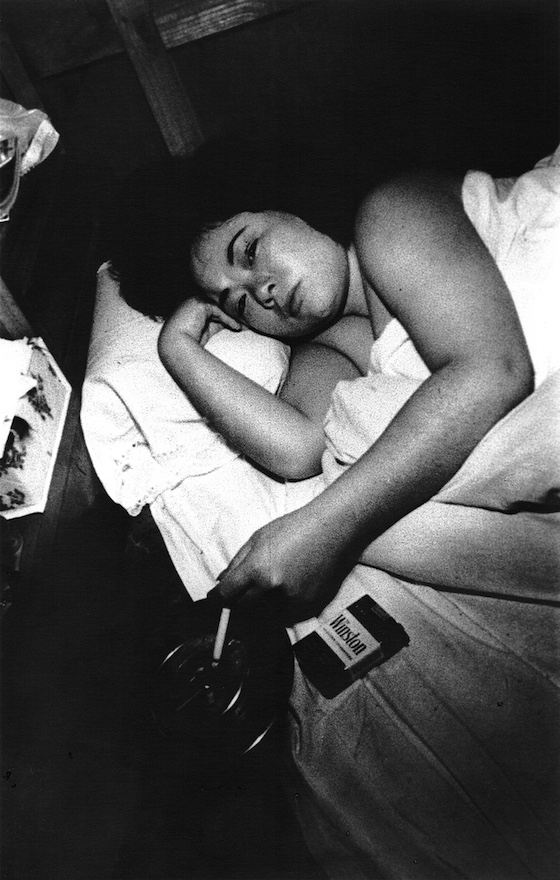

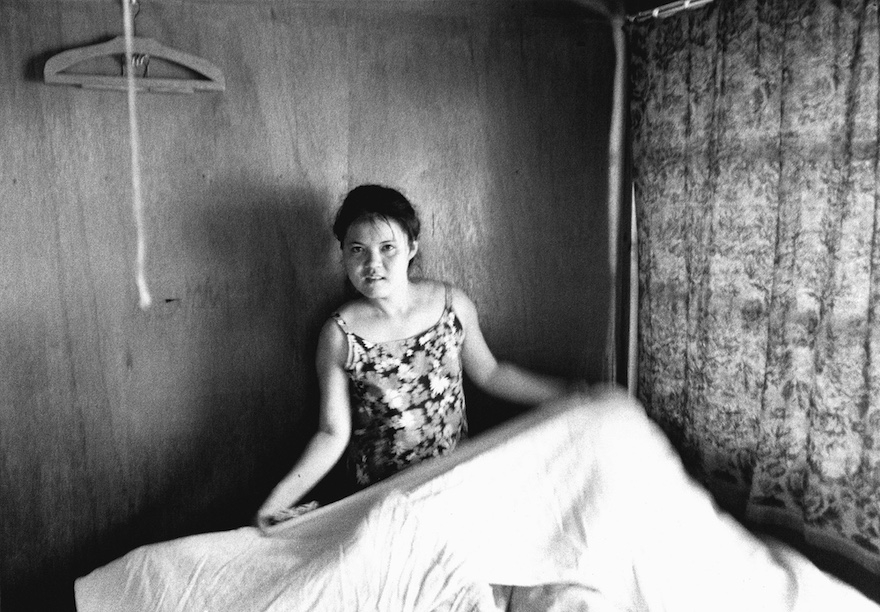

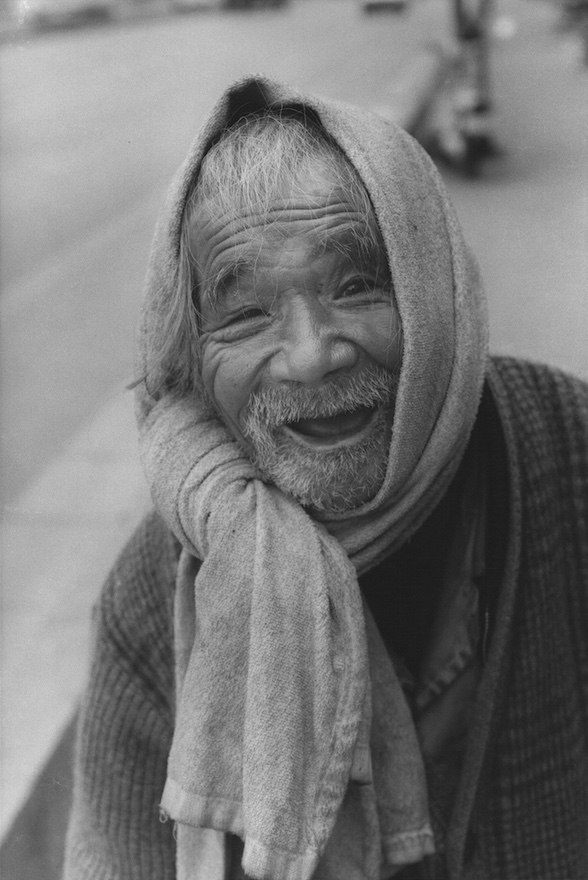

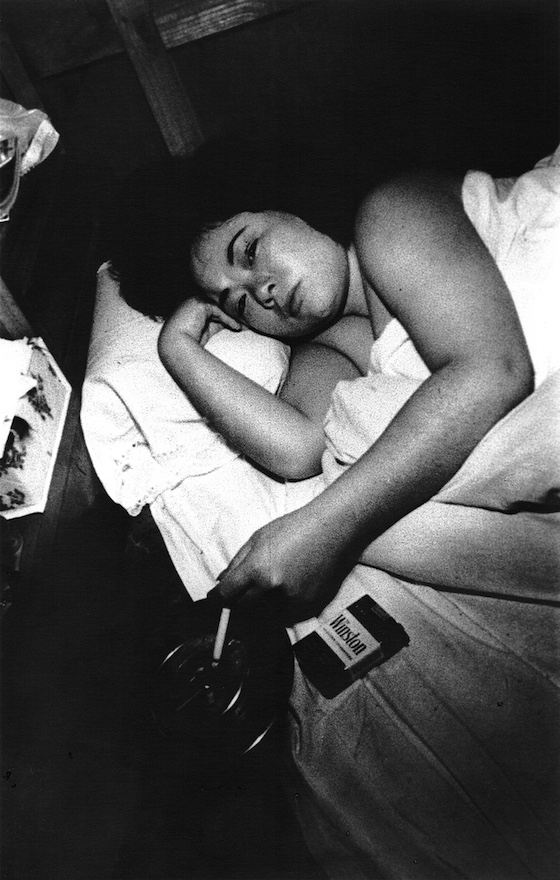

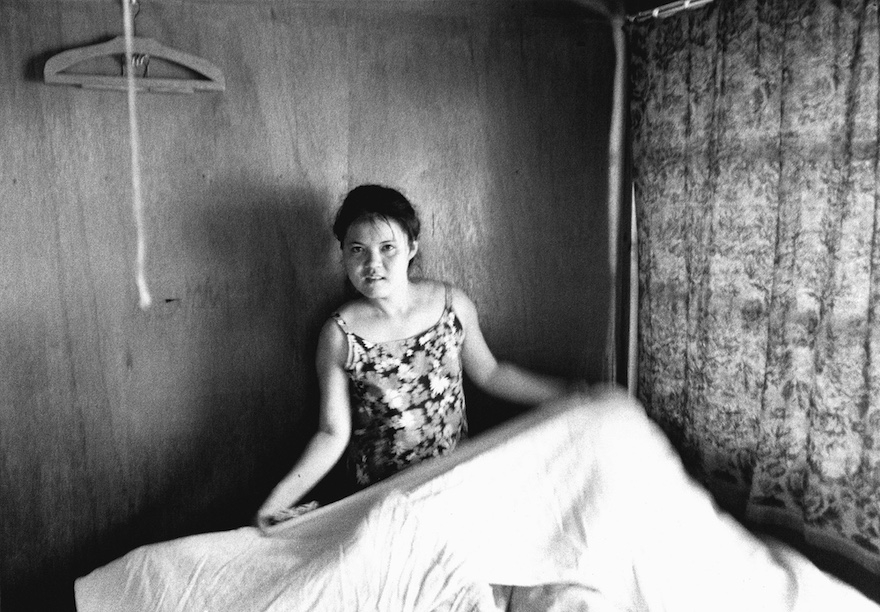

In addition to the almost total absence of meta-photographic qualities, one of things that distinguishes Heshiki-style konpora from mainland Japanese konpora is that U.S. military bases hardly ever appear as subjects.11 Instead, Heshiki’s work depicts such things as the Japanese government’s callous destruction of common burial sites of the war dead and caves. Because it is clear that the callousness of the Japanese “national polity” government stems from the denial of Japan’s defeat, and common burial sites and caves in particular are vivid scars of this defeat. Heshiki’s camera also captures “people on the beaches” and “working women” of the Ryukyu Islands. One of the reasons why Yagi no hai had such an impact in 2007 was that (like Tomatsu Shomei’s 11.02 Nagasaki) it showed that more than 20 years after Japan’s defeat, these people were still leading lives so poor it left one speechless, but more than that, there appeared to be no suppression whatsoever. I am not talking about the kind of humanism that recognizes the dignity of people who never forget to smile despite being poor. Here, a world acting out in real life Sakaguchi Ango’s “Darakuron” (Discourse on decadence) stretched out. Because it had lost all its dreams, Okinawa, which had been abandoned by the mainland and fallen under the control of the U.S. military, was free from the “as it is” dream compelled by the “national polity,” and above all else could not be anything other than Okinawa.12

In addition to the almost total absence of meta-photographic qualities, one of things that distinguishes Heshiki-style konpora from mainland Japanese konpora is that U.S. military bases hardly ever appear as subjects.11 Instead, Heshiki’s work depicts such things as the Japanese government’s callous destruction of common burial sites of the war dead and caves. Because it is clear that the callousness of the Japanese “national polity” government stems from the denial of Japan’s defeat, and common burial sites and caves in particular are vivid scars of this defeat. Heshiki’s camera also captures “people on the beaches” and “working women” of the Ryukyu Islands. One of the reasons why Yagi no hai had such an impact in 2007 was that (like Tomatsu Shomei’s 11.02 Nagasaki) it showed that more than 20 years after Japan’s defeat, these people were still leading lives so poor it left one speechless, but more than that, there appeared to be no suppression whatsoever. I am not talking about the kind of humanism that recognizes the dignity of people who never forget to smile despite being poor. Here, a world acting out in real life Sakaguchi Ango’s “Darakuron” (Discourse on decadence) stretched out. Because it had lost all its dreams, Okinawa, which had been abandoned by the mainland and fallen under the control of the U.S. military, was free from the “as it is” dream compelled by the “national polity,” and above all else could not be anything other than Okinawa.12

——————————–

——————————–

1. The English word “tragedy,” the German word Tragödie and the French word tragédie all derive from the Greek word tragōidia (τραγῳδία), which is a compound of tragos (τράγος), meaning “goat,” and ōidē (ᾠδή), meaning “song.” 2. A theory heard from a gallerist in the form of a remark by Heshiki. On the other hand, there is actually a culture of eating goat’s lungs, including in Okinawa, where “Yagi-jiru [goat soup] is made by cooking together the meat, bones and internal organs of goats, with everything consumed without exception.” (Report on the Fact-Finding Investigation into the Use of Goat Products II, FY2000 Goat Products Utilization Promotion Project) Though I am uncertain of the authenticity of the yagi-jiru recipe—or if genuine yagi-jiru actually exists—since the title of the photobook is Yagi no hai, it is probably true that the lungs were distinguished from other internal organs, which is to say they were regarded as a symbol of “things left untouched.” 3. P.39 of Yagi no hai features a photograph of a male goat in heat on its way to an abattoir. It is titled, “On its way to be sold, on its way to be slaughtered, shadow fire on the move.” 4. Numa Shōzō’s pornographic science-fiction novel (1956–1958/1970) tirelessly narrating sado-masochistic, scatological fantasies of the humiliated Yapoo (aka. Japanese) people in a near-future world of white Anglo-Saxon supremacy. “Yapoo” refers to Yahoo in Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels. 5. Shimizu Minoru, “Puroboku to konpora—’Nihon shashin no 1968’ ten” [Provoke and konpora: the “1968—Japanese Photography” exhibition] in Dijitaru shashin ron [On digital photography] (University of Tokyo Press, 2020), 70. For a detailed discussion of “konpora photography and the U.S.” see Chapter 2 in Tomiyama Yukiko, “Konpora shashin: Nihon shashinshi ni okeru ‘nichijō,’ 1970 nen zengo o chūshin ni” [Konpora photography: “Everyday life” in the history of Japanese photography, with a focus on the period around 1970] (PhD diss., UTokyo Repository, pdf). 6. One of the strongest champions of the “everyday” of konpora photography, which is to say its “jour”nalistic qualities or “everydayness,” was Tosaka Jun. As early as 1934 he was criticizing the “as it is reality” of surrealism, explaining that it was in everyday life that one should see true, actual reality, and that in this sense criticism should be journalistic. Tosaka Jun, “Nichijōsei ni tsuite” [On everydayness], Tosaka Jun serekushon [Tosaka Jun selection], ed. Shumei Rin, (Heibonsha Library 863, 2018), 222. Also see Note 58, p. 237 in the aforementioned dissertation by Tomiyama. 7. “Cultural Currency 11: Alternatives to ‘Landscape’ (Part 3)”

8. A deliberate, awakened attitude to negative elements is not inconsistent with suppression. Suppression affirms denial as denial and excludes the possibility of moving beyond what Orwell and Žižek refer to as “doublethink.” “A national polity based on the U.S. and the imperial family is of course worthless. But is there really another national polity Japan can choose?” 9. The three ways Okinawa is written in the Japanese title can be interpreted as referring to pre-war Okinawa, Okinawa during the occupation, and Okinawa after its return to Japan. In other words, Okinawa as a region in East Asia in a different cultural sphere and with a different history than Japan, Okinawa under the control of the U.S. military, and the Okinawa that was absorbed into the Japanese “national polity” and rapidly Americanized after Japan’s defeat. 10. Heshiki Kenshichi, Yagi no hai: Okinawa 1968–2005 (reprinted edition, Kageshobo, 2018), 2. 11. Except for “Lookout for demonstration march (Kadena Air Base 1970),” 27; “B-29s are still here today (Kadena 1970),” 41; and “At the Kadena Carnival (Kadena Air Base 1970),” 52, in Heshiki Kenshichi, Yagi no hai.

The almost complete lack of photographs of bases may reflect the meta-photographic nature of Heshiki’s photography. 12. One could probably cite Watanabe Katsumi, Shinjuku guntō-den 66/73 (Baragaho, 1973) as a photobook from mainland Japan that can be compared with Yagi no hai. The images from among the “depraved” people who gathered in the areas of Shinjuku that retain the appearance of a black market make a nice contrast to Kurata Seiji’s FLASH UP, for example.

——————————–

Shimizu Minoru

Critic. Professor, Doshisha University. “Heshiki Kenshichi: Lungs of a Goat” was held at The Third Gallery Aya from January 27 to February 24, 2024.

*

The cover of Tomatsu Shomei’s photobook Okinawa, Okinawa, Okinawa (Shaken, 1969) features the famous words, “The bases are not in Okinawa, Okinawa is in the bases.”9 Responding to this, Heshiki Kenshichi wrote:

I want to believe that the bases are in Okinawa. These photographs were taken from around the time of the “return” of Okinawa, which is made up of around 47 inhabited islands. I think that through this photobook, people will be able to get a sense of what the history of Okinawa, Okinawa, and the people of Okinawa are.10

1. The English word “tragedy,” the German word Tragödie and the French word tragédie all derive from the Greek word tragōidia (τραγῳδία), which is a compound of tragos (τράγος), meaning “goat,” and ōidē (ᾠδή), meaning “song.” 2. A theory heard from a gallerist in the form of a remark by Heshiki. On the other hand, there is actually a culture of eating goat’s lungs, including in Okinawa, where “Yagi-jiru [goat soup] is made by cooking together the meat, bones and internal organs of goats, with everything consumed without exception.” (Report on the Fact-Finding Investigation into the Use of Goat Products II, FY2000 Goat Products Utilization Promotion Project) Though I am uncertain of the authenticity of the yagi-jiru recipe—or if genuine yagi-jiru actually exists—since the title of the photobook is Yagi no hai, it is probably true that the lungs were distinguished from other internal organs, which is to say they were regarded as a symbol of “things left untouched.” 3. P.39 of Yagi no hai features a photograph of a male goat in heat on its way to an abattoir. It is titled, “On its way to be sold, on its way to be slaughtered, shadow fire on the move.” 4. Numa Shōzō’s pornographic science-fiction novel (1956–1958/1970) tirelessly narrating sado-masochistic, scatological fantasies of the humiliated Yapoo (aka. Japanese) people in a near-future world of white Anglo-Saxon supremacy. “Yapoo” refers to Yahoo in Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels. 5. Shimizu Minoru, “Puroboku to konpora—’Nihon shashin no 1968’ ten” [Provoke and konpora: the “1968—Japanese Photography” exhibition] in Dijitaru shashin ron [On digital photography] (University of Tokyo Press, 2020), 70. For a detailed discussion of “konpora photography and the U.S.” see Chapter 2 in Tomiyama Yukiko, “Konpora shashin: Nihon shashinshi ni okeru ‘nichijō,’ 1970 nen zengo o chūshin ni” [Konpora photography: “Everyday life” in the history of Japanese photography, with a focus on the period around 1970] (PhD diss., UTokyo Repository, pdf). 6. One of the strongest champions of the “everyday” of konpora photography, which is to say its “jour”nalistic qualities or “everydayness,” was Tosaka Jun. As early as 1934 he was criticizing the “as it is reality” of surrealism, explaining that it was in everyday life that one should see true, actual reality, and that in this sense criticism should be journalistic. Tosaka Jun, “Nichijōsei ni tsuite” [On everydayness], Tosaka Jun serekushon [Tosaka Jun selection], ed. Shumei Rin, (Heibonsha Library 863, 2018), 222. Also see Note 58, p. 237 in the aforementioned dissertation by Tomiyama. 7. “Cultural Currency 11: Alternatives to ‘Landscape’ (Part 3)”

8. A deliberate, awakened attitude to negative elements is not inconsistent with suppression. Suppression affirms denial as denial and excludes the possibility of moving beyond what Orwell and Žižek refer to as “doublethink.” “A national polity based on the U.S. and the imperial family is of course worthless. But is there really another national polity Japan can choose?” 9. The three ways Okinawa is written in the Japanese title can be interpreted as referring to pre-war Okinawa, Okinawa during the occupation, and Okinawa after its return to Japan. In other words, Okinawa as a region in East Asia in a different cultural sphere and with a different history than Japan, Okinawa under the control of the U.S. military, and the Okinawa that was absorbed into the Japanese “national polity” and rapidly Americanized after Japan’s defeat. 10. Heshiki Kenshichi, Yagi no hai: Okinawa 1968–2005 (reprinted edition, Kageshobo, 2018), 2. 11. Except for “Lookout for demonstration march (Kadena Air Base 1970),” 27; “B-29s are still here today (Kadena 1970),” 41; and “At the Kadena Carnival (Kadena Air Base 1970),” 52, in Heshiki Kenshichi, Yagi no hai.

The almost complete lack of photographs of bases may reflect the meta-photographic nature of Heshiki’s photography. 12. One could probably cite Watanabe Katsumi, Shinjuku guntō-den 66/73 (Baragaho, 1973) as a photobook from mainland Japan that can be compared with Yagi no hai. The images from among the “depraved” people who gathered in the areas of Shinjuku that retain the appearance of a black market make a nice contrast to Kurata Seiji’s FLASH UP, for example.

——————————–

Shimizu Minoru

Critic. Professor, Doshisha University. “Heshiki Kenshichi: Lungs of a Goat” was held at The Third Gallery Aya from January 27 to February 24, 2024.