AiR Report : My Paris Residency Part 1 -

How will “the beloved woman” change?

By Kajihara Mizuki

The Cité internationale des arts is an artist-in-residence program that has been operating since 1965 in the Marais district of Paris, France, and is open not only to artists, but to creatives in many fields including musicians, dancers and writers. Located facing the Seine where the river flows on either side of the Île Saint-Louis, it is a huge facility capable of hosting more than 200 residents at one time. Through “Artist in Residence program in Paris 2020/2021” cosponsored by the Chishima Foundation for Creative Osaka, the Kyoto Art Center, Villa Kujoyama and the Institut français, I was given the opportunity to stay at the Cité for three months from October 9.

Every Wednesday, artists can choose to present their work at an “open studio,” while music, dance and other live performances are held in the basement hall. There are also extended exhibitions in the gallery, making for a busy schedule of events that provide welcome opportunities for interactions with other residents. I both appreciate the incredible value of this opportunity to live and work overseas given the impact the coronavirus pandemic has had on so many cultural activities since 2019, and am amazed that this environment where artists from various countries can come together exists in the first place.

Cité internationale des arts, Paris. Photo by Kajihara Mizuki

◉

My main interest is in Western music, and my works explore its history and background.

For my 2019 work «The Libertine Punished or…», inspired by an episode relating to the creation of the opera Don Giovanni, I travelled by bicycle from Vienna to Prague following the route of Mozart’s own journey. And for my 2020 work «Simple and soft, but not so slow.», I staged a performance in which at each station between Kyoto and Nagasaki, I played a piece by the Dutch composer Jonny Heykens known in Japan as the melody that accompanies in-car announcements on certain railway lines.

In both these works, I was inspired by the history and background of the compositions concerned and sought to understand them through my own physical experience, but I also wondered if they could be converted into different languages.

Simple and soft, but not so slow. (2020) Kajihara Mizuki

The project I am working on in Paris involves playing “Chinese whispers with music” using phrases from Symphonie fantastique, a work written in 1830 by the French composer Hector Berlioz (1803–1869). Symphonie fantastique occupies an important position in musical history through its use of the technique known as “idée fixe” (fixed idea).

In 1827, after attending a performance of the play Hamlet at the Odéon Théâtre in Paris’s 6th arrondissement, Berlioz declared that it had “struck me like a thunderbolt.” Not only was his high regard for Shakespeare reconfirmed, but above all the sight of Harriet Smithson, the popular Irish actress who played the role of Ophelia, became indelibly etched in his mind. [*1]

Théâtre de l’Odéon, Paris. Photo by Kajihara Mizuki

It was from the passionate feelings of love Berlioz experienced at this time that Symphonie fantastique was born. The work was first performed at the Paris Conservatoire, on which occasion Berlioz handed out to the audience a program containing a love story he had written himself. It told of a young artist who, tormented by feelings of love for the woman of his dreams, tries to commit suicide. This ideal woman gradually takes on a bewitching aspect, ultimately leading to a dream of a witches’ sabbath where a grotesque melody is played.

In the program, Berlioz explains that the melody that recurs throughout the work signifies “the beloved woman” and that the other characters and their expression are similarly connected to particular melodies.

The introduction to the program reads:

The composer’s intention has been to develop various episodes in the life of an artist, in so far as they lend themselves to musical treatment. As the work cannot rely on the assistance of speech, the plan of the instrumental drama needs to be set out in advance. The following programme must therefore be considered as the spoken text of an opera, which serves to introduce musical movements and to motivate their character and expression. [*2]

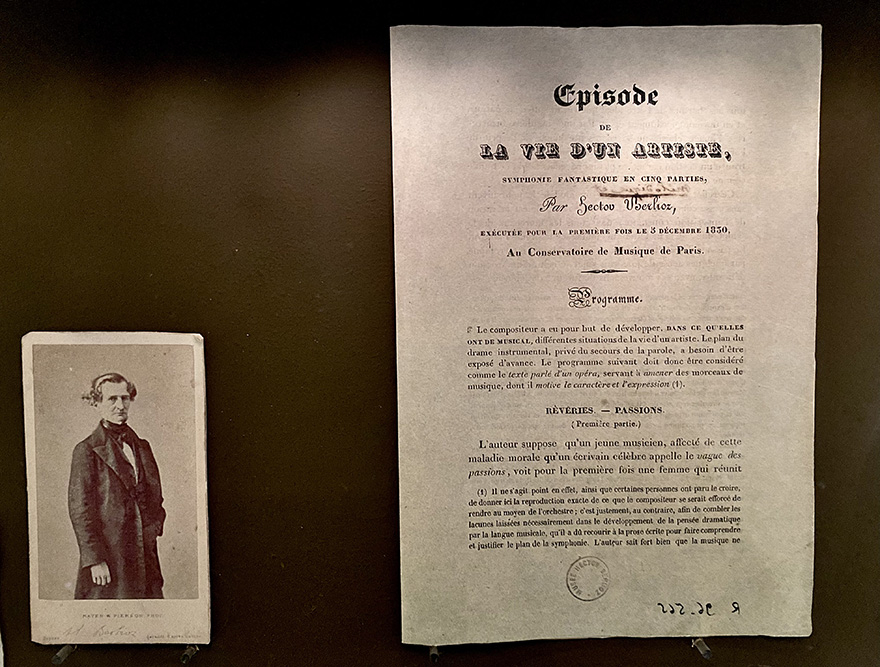

Episode in the life of an artist. Symphonie fantastique in five parts, Programme 1830, Musée Hector-Berlioz. Photo by Kajihara Mizuki

This technique of conditionally linking certain subjects and melodies is known as “idée fixe”, and to the extent that it involves “listening to music semantically in accordance with the wishes of the composer” it was extremely innovative for the time. [*3]

After being adopted by Richard Wagner, who in 1839 at the age of 26 attended a performance in Paris of Berlioz’s symphony Roméo et Juliette, which had a huge influence on him, the technique developed into what is known today as a “leitmotif.” Through Wagner’s operas, people came to think more deeply about “the relationship between music and language.” [*4]

I became interested in this “attachment of meaning to music” as well as in “the relationship between music and language” passed on to Wagner, out of which came the concept for this project.

In my “Chinese whispers” game, I take the melody from Symphonie fantastique that signifies “the beloved woman” as the starting phrase and record how it changes as it is passed from one person to another.

Model of «Symphonie fantastique» Concert hall of the Consarvatoire de Paris in 1830, Musée Hector-Berlioz. Photo by Kajihara Mizuki

[*1] Chapter 18 of Berlioz’s Memoirs.

[*2] Hector Berlioz, “Symphonie Fantastique: the symphony’s programme (1845 and 1855 versions),” The Hector Berlioz website, trans. Michel Austin, accessed December 8, 2021,

[*3] “Learn about music history: 19th-century music,” MUSIC PAL, accessed November 1, 2021,

[*4] Kuno Keiichi, Berloiz (Ongaku no Tomo Sha, 1967).

◉

One month has passed since I arrived in Paris.

I have conducted the game several times in rehearsals and, as expected, the melody easily changes and the anticipated divergences evoke good-natured laughter. As well, I have come to realize that because it is a game that does not use language, I can get many people to join in.

In an effort to get even more people to participate in the game, I decided to take part in the Wednesday “open studio.” Properly speaking, an open studio involves inviting the public into one’s own work space, but after explaining that one of the aims of my project is to invite a wide range of participants, I was able to hold it as a workshop in one of the shared spaces.

So, how will “the beloved woman” melody change? In my next report, I hope to describe what happened.

My Paris Residency Part 2 – The Return to Life or…My Paris Residency Part 3 – A view from a hill, a view from a window

Kajihara Mizuki

Artist. Graduate of the Contemporary Art and Photography Course, Kyoto University of the Arts (former Kyoto University of Art and Design). Has completed the Global Seminar at KUA’s Graduate School.