AiR Report : My Paris Residency Part 3 - the last

A view from a hill, a view from a window

By Kajihara Mizuki

It was during the excitement surrounding the 1937 International Exposition that calls to turn Paris into the capital of the arts first arose. In 1965, theCité internationale des artswas established in the Marais district based on the concept of opening the city to artists from around the world.

Later, in the early 1970s, the Cité inaugurated a second site on Paris’s tallest hill, Montmartre. Named Villa Radet, it is a stone’s throw from the Sacré-Coeur and surrounded by a garden within a magnificent forest. To date, some forty artists have completed residencies at this facility inside a historic building.

After exiting Lamarck-Caulaincourt, a Paris Métro station on the other side of Montmartre named after two 18th-century figures, visitors negotiate a steep incline to reach the modest Villa Radet, which stands across the street from a statue of a famous chanteuse. While surrounded by Rue de l’Abreuvoir, which is often crowded with tourists, the grounds have an air of quiet solemnity as if cut off from the hubbub of the city.

The project I worked on at the Cité was inspired by the work of Hector Berlioz (1803-1869), who was active in Paris in the 19th century. In particular, I focused on the technique of “idée fixe” (fixed idea) that Berlioz established. I was interested in the impact this technique of linking a certain melody to a particular meaning had on music from the 19th century onwards and how it even transcended music to take on a linguistic role.

Berlioz established this technique in 1830 when he composed Symphonie fantastique as an expression of his love for the actress Harriet Smithson. After a short stay in Rome from the end of 1830 to the fall of 1832, he unveiled a sequel to Symphonie fantastique titled Lélio, or the Return to Life. The following year, 1833, Berlioz married Smithson, and for two years from 1834 the couple lived Montmartre.

Photo by Kajihara Mizuki

Around five minutes on foot from Villa Radet, the former home of Hector and Harriet Berlioz is located partway up a long flight of steps, overlooking central Paris. Reading Berlioz’s memoirs covering this period, one gets a sense of how Montmartre was a quiet area on the outskirts of Paris, something difficult to imagine given it is now crowded with souvenir shops and people touring movie locations.

Despite this, there are still reminders that this entire area was once farmland. After passing through the front gates at Villa Radet, an expanse of splendid greenery opens up before you. The impression, when lush vegetation filled my field of vision, was so different from the street outside where tourists paraded in ranks that I almost forgot where I was.

◉

At the Cité site near the Pont Marie, open studios are held every Wednesday. These often trigger lively conversations among residents who meet up by chance leading to new developments. It was while talking to an artist I met at an open studio in November that I decided to participate in a group exhibition organized by a Korean artist staying at Villa Radet in Montmartre.

At the time, I only had one month left in my Paris residency. I decided to present as an artwork the interim results of my project involving playing “Chinese whispers” using a phrase from Symphonie fantastique, and set about transcribing the voices I had recorded.

Organized by Mona Young-eun Kim, an artist in residence at Villa Radet, “No Home Radius 20,000 km” was a group exhibition involving 21 artists including those based in Paris as well as Cité residents such as myself. It was held from December 24 to early January during the holiday season when Montmartre falls completely silent.

Photo by Mona young-eun Kim

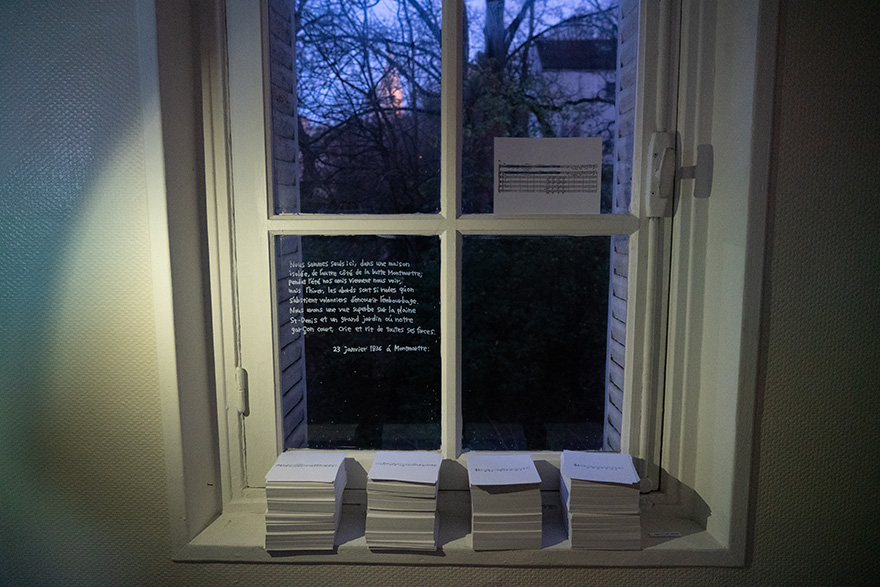

The many-sided room at Villa Radet that served as the exhibition venue had windows on each wall. I chose to install my work by a window that faced the apartment where Berlioz once lived.

First performed at the Paris Conservatoire in 1830, Symphonie fantastique is known for its use of the technique called “idée fixe”, in which subjects and melodies are conditionally linked. In the work, an actual story written by Berlioz himself was used, and a certain melody is considered to represent Harriet Smithson (“the beloved woman”). One could call this music premised on explaining things using words, or a proposal for “listening to meaning.” In other words, I interpret the technique of “idée fixe” as an attempt to search for the boundary between “words” and “music.” For example, if one experiences like Berlioz a feeling of “love” for a particular person, how can that be converted into “sound”? How much information can sound contain on its own? How can that information be conveyed to others?

Based on these questions, I devised a game of “Chinese whispers” using the melody from Symphonie fantastique that represents “the beloved,” and during my residency in Paris got various people to take part in this game. As the sound was passed from person to person, I recorded how the melody that originally signified “the beloved” was perceived and changed. This was the project I undertook in Paris.

In short, the result was that the roughly five-second-long melody changed dramatically depending on the person who received it. Only a few people reproduced both the key and time accurately, while most either simplified it or rendered it more complex.

For the exhibition, I transcribed and printed out on paper four of the results of the “Chinese whispers” games I conducted during my residency and arranged them together. Visitors were able to take home the sheets of music. On the window facing the apartment where Berlioz once lived I reproduced the following words from a letter he wrote in 1836:

Photo by Mona young-eun Kim

“We are alone here, in an isolated house, on the other side of the hill of Montmartre; in summer our friends come to visit us, but in winter the approaches are so strenuous that people prefer not to get stuck in the mud. We have a superb view over the plain of Saint-Denis and a large garden where our boy runs around, shouting and laughing with all his energy” [*1]

[*1] Hector Berlioz, “Montmartre / Choix de lettres de Berlioz: 1834-1836 / À Édouard Rocher, 23 janvier (CG no. 458, de Montmartre)” The Hector Berlioz website, accessed December 8, 2021,

◉

One day during the exhibition, the concierge at Villa Radet, who was visiting the venue, recommended I meet a certain musician. This musician had been living for some time in a house visible from the window where I was displaying my work. As soon as I got back to my studio I listened to some recordings of his performances, after which I decided to pay him a visit with a letter and a bunch of flowers.

Born in Bulgaria in 1926, pianist Ventsislav Yankov moved to France in 1946, soon after the end of World War II. He went on to give numerous concerts around the world and was appointed professor emeritus at the Conservatoire of Paris. His house was surrounded by a beautiful garden with an abundance of flowering plants.

After passing through the airy entrance hall, I found myself in a room with a large grand piano. Yankov was sitting on a sofa next to the piano, from where he greeted me. I remember that the space was packed with countless musical scores, books, CDs and other items. Among them were black-and-white photographs of Yankov dressed in a tuxedo. The items, so numerous they almost filled the room to overflowing, seemed to speak to the length and richness of the owner’s career as a musician. I handed over the letter and flowers, after which Yankov spoke to me for around ten minutes. Though our meeting was brief, it was the most memorable experience of my three-month residency in Paris.

The exhibition opening took place on the evening of December 24 and attracted a lively crowd of people. It being Christmas Eve, after enjoying a potluck party including wine in a cask with a tap, I walked with the other participating artists in the dark towards the Sacré-Coeur.

Against the backdrop of restrictions on social contact due to the spread of Covid-19, this group of artists had ended up spending Christmas 2021 together in Paris, though each had followed a completely different path to get there. For me, this exhibition that explored home, family and our own place with respect to them seemed to have a pluralistic expansiveness that extended out into all manner of time and place.

Photo by Kajihara Mizuki

Photo by Kajihara Mizuki

Photo by Kajihara Mizuki

After New Year, things began to pick up again in the Marais district where the Cité is located. I spent the time until the day of my departure talking over coffee with the other artists I had met there about our practices, remaining busy right up until my return to Japan.

Looking back on it now, as someone experiencing a residency overseas for the first time, it also seems as if I spent most of my time frantically dealing with such commonplace realities as learning about other cultures and trying to communicate with people.

Since my Paris residency, my motive for making art has changed slightly. Until now, I have been interested in the symbolism of music and its historical background as well as the biographies of composers, making artworks that include elements of physical performance. However, as a result of this residency, my interest has begun to shift more towards the relationship between “sound” and “language (i.e. means of communication).” Western classical music, which introduced regularity and recordability to sounds, themselves devoid of substance, is the starting point of my interest. For me, “sounds” are things that can only be grasped in certain moments and certain places. In the short term, how can I make the most of my experience of actually living in Paris for three months and getting a taste of the city’s history while listening to its “sounds”? I hope to find the answer to this question by continuing to pursue my art practice.

My Paris Residency Part 1 – How will “the beloved woman” change?My Paris Residency Part 2 – The Return to Life or…

Kajihara Mizuki

Artist. Graduate of the Contemporary Art and Photography Course, Kyoto University of the Arts. Has completed the Global Seminar at KUA’s Graduate School.