This may be the Land of the Free, but there's plenty cause for righteous indignation

Technical notes for a stateside sojourn, plus a little extra (4) part 2 – the last

By Kanai Manabu

Examining resource material / visiting places

Let’s assume you’re now able to go around looking at the works you want to see. My interest, as I wrote earlier, lies in the triumvirate of Frank Stella, Merce Cunningham, and Black Mountain College (BMC), so to explore the background to the relevant art practice in the ’60s and ’70s, inevitably I need to examine a variety of archival material. When it comes to the collaborations between Stella and Cunningham in particular, because obviously there is no chance to see the genuine article in person, I have to rely on film documentation of the performances, and with the BMC being closed since the 1950s, if I want to obtain more detailed knowledge than can be gleaned from the books, essays and so on in general circulation, I need to visit the archive center close to there. There are a number of archives in the US dealing with all three of the aforementioned, but here I will explain about doing research in the New York Public Library, and State Archives of North Carolina.

New York Public Library for the Performing Arts

Many of you will be familiar with the main building of the New York Public Library in Midtown from movies, as it has featured in quite a few, but in addition to this main library and its branches around Manhattan, there are also four dedicated research libraries. The main archives of Cunningham and the Merce Cunningham Dance Company (MCDC) are kept in the special collection of one of these, the Library for the Performing Arts. The LPA is located inside the Lincoln Center for the Performing Arts—a hub for the performing arts in the city containing the New York State Theater (now the David H. Koch Theater) home to the New York City Ballet, the David Geffen Hall where the New York Philharmonic is based, and the Juilliard School—and sits snugly between the Metropolitan Opera House and Lincoln Center Theater.

Accessing this research library requires opening two types of library account. One is an ordinary account for library use, and the other a research account for searching and accessing material in the special collections. In both cases, you set up a temporary account online by providing basic info like address and contact details, then take proof of address etc. to your closest library, where they will issue you a user card. Your preparations for library use are thus complete. You use this account to log into the search system, and look for the material you want. (As an aside, I was astounded to find I had full access to JSTOR from home using an ordinary NYPL account. No fortnightly limit on the number of articles viewed, and of course, all absolutely free.)

When it comes to looking for material, general books and so on can be searched the usual way to find what you’re interested in but (as those who’ve had anything to do with archives will know), for archival material, you start searching from a list of archival material called a “Finding Aid” for each type of material. Note that some archival material on particular research topics may span multiple archive collections, so you will end up traversing several Finding Aids to find it. For example, as you’ll discover if you initiate a search in the archive search system, in the case of Merce Cunningham, three types of archive collection come up: (1) choreography material, (2) material related to the MCDC, and (3) additional MCDC material, with details on what is included in each and how they are structured, so you search for the material you want within these. In my case for example, I use this Finding Aid system to conduct exhaustive searches of material seemingly related to 1967’s Scramble, BMC material from records covering 1948-53, and material on Elizabeth Jennerjahn and Kathleen Harris, who taught at BMC, and upon finding what I want to access, add the material to My List in the search system, in order to in the first instance, compile a list of resources to check.

This is only my experience, but to be frank, it would be no exaggeration to say that your success with archival research will depend on how well you are able to work with the Finding Aid tool. Obviously you start with information you already know, matching decade, the person’s name, location, and type of documentary material to find boxes and files that look like they might contain what you’re after, however the different archives have quite a few quirks in how they compile material, and the fact is that having cast your net, it will take a little while to start working more intuitively. There is also material that though held by the library, requires access permission from some other entity like a trust or foundation, which adds another layer of complexity. So what do you do then? The best thing to do first in this case, in my view, is get reference services help from a librarian. Due in part to Covid you can now talk to librarians over video chat about finding material, without even going to the library. I had compiled somewhat of a list from Finding Aids before leaving Japan, but on consulting the reference service I found that the LPA librarians, being the pros among pros, were able to add a stream of relevant material to my list, and what’s more, before I knew it had connected me to the director of the Merce Cunningham Trust, so ultimately I was able to deal with the Trust and get access to film and choreographic material administered by them as well. It really was a perfect example of “ask and ye shall receive.”

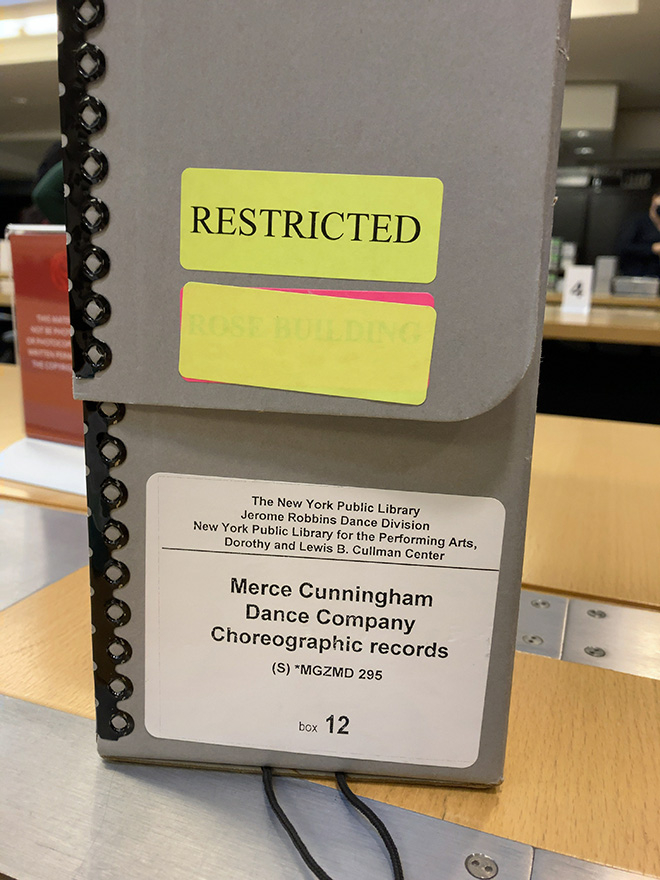

Archive box containing MCDC choreographic materials. Trust permission is required for access and materials are not to be copied.

Once you have something of a list, it is finally time to come face to face with the material. This means either sending a request for it through the system, or in the case of the special collections, sending an e-mail with the reference number for the material, and the date you actually want to visit the research center. A few days later you will be contacted by a librarian, and if there are no issues you’ll receive confirmation of the material to be prepared for you, and details of your appointment at the research center. On the day you simply take your library card and head to the research center. Be sure to bring a laptop and camera (smartphone with camera). Once at the LPA you undergo a bag check at the entrance, then take the elevator up from the general archive floor to the special collection reading room on the third floor. To protect the collection bags are not allowed in the reading room (much like the National Diet Library in Tokyo), so you leave your belongings at the coat check, borrow a clear plastic bag, and place what you need in it before heading in. Archival material access that requires a prior request for the material and an appointment may involve opening the material right at the back of the room, under the guidance of a librarian. Once you’ve scanned your user card and had your appointment confirmed, you can pick up the archive box you asked for. Then all you need to do is settle down and explore the material, taking care to heed the conditions. In saying that, there is a time limit, so for resources able to be photographed, it’s more likely you’ll find yourself opening the files you’re looking for, photographing everything in them and forwarding the data to your laptop, repeating this over and over, then taking your time to pick out the usable gems once you’ve gone home and sorted through the photos. Though I must say viewing and putting all those photos you’ve taken into some kind of order is quite a slog…

I will also say though that I was stunned to open the archive box for Scramble and find fabric samples from set and costumes—oh the colors, so much more vivid than I’d imagined from the black and white video; the texture of the materials! The address of the fabric store was only two blocks from where Stella had his studio (probably his second in New York). The fact that Stella was using Benjamin Moore paints made me wonder if he was indeed sourcing his materials from nearby at this time. Such nuggets of information are typical of the intriguing treasures one can unearth in archives.

BMC Lake Eden campus since the 1940s. The Coker-designed building also still exists.

A visit to Asheville, North Carolina

One of the main archives for BMC is in Asheville in the west of the state of North Carolina. Asheville is next door to Black Mountain, where BMC was situated, and is the county seat of Buncombe County, NC. I flew from New York to Charlotte, then rented a car and drove for about another two hours to get there. Asheville is home to the Black Mountain College Museum + Arts Center(BMCM+AC), which has displays covering BMC’s history and collection; the Asheville Art Museum, which in recent years has been compiling a digital archive of BMC; and a little way out of the city, the North Carolina State Archives Western Regional Archives (WRA), which contain archival material on BMC. Incidentally, the campuses and buildings that were home to BMC in the ’30s and from the ’40s onward can still be found in Black Mountain.

I went down and conducted my first lot of research in November last year to coincide with a tour being run of the Lake Eden campus.[*1] There was no need to register to access the archives, but as my time was limited, I contacted the archivist in advance to say who I was, what I was researching and to what purpose, and having checked the Finding Aid for BMC archival material from the WRA search system, told them when I was coming and requested the material. I had already visited there in 2019 and had contact details for the archivist, who seemed delighted to hear from me again after two years of the pandemic. I left New York early in the morning and arrived in Asheville early afternoon. Covid issues meant that the WRA unfortunately closed at 2pm, so I spent the first day viewing an exhibition at BMCM+AC, and driving to the YMCA Blue Ridge Assembly that was BMC’s first campus. The next day it was down to business. The method for accessing materials was not much different to that of the LPA in New York: sign in at reception, proceed to the second floor where the reading room for the archives is located, place bag and/or any unnecessary personal belongings in a locker, enter the room, where the archivist in charge is waiting. From 9am open as many boxes from the collection as time allows, and take photos.

[*1] Part of the BMC survey was supported by a joint research project of the Tama Art University. I would like to thank for this support.

North Carolina State Archives Western Branch.

View of the reading room.

The BMC archive collections held by the WRA are split into several parts, so I identify the material I want in the search system of each, and check any collection Finding Aids that are picked up, making a list of material that looks relevant. Some things in the collections are especially central to any study of the subject, including (1) Various records of BMC as a university, such as lists of teaching staff and students, financial statements, records of meetings, records of student enrolment and leaving, (2) Material gathered in research conducted by Martin Duberman in the ’60s and ’70s (compiled in Duberman’s Black Mountain: An Exploration in Community), (3) The BMC Research Project undertaken by the North Carolina Museum of Art between 1970 and ’73, and (4) The collection amassed via the BMC Project carried out independently by Mary Emma Harris, author of The Arts at Black Mountain College (Harris was also a central figure in the BMC Research Project). There are also several bodies of material donated by individuals associated with BMC worth examining as well depending on their content. Not surprisingly each collection has its own features (for example if you want to know in detail about any changes to BMC’s financial situation as a college, or the number of students, check the college records; if you’re interested in learning about the experiences of artists and students associated with BMC, and what they had to say, see the collections amassed by the likes of Duberman and Harris, which include a lot of interviews), so it comes down to keeping a close eye on the Finding Aids and getting advice from the librarians to refine your searches. I have found a number of interesting resources, but am still only partway through the process. Managing to speak directly with Harris in New York last year was also a great help. I intend to embark on my second research trip fairly soon.

Dining Hall Building at BMC Lake Eden Campus.

On the last day of my stay in Asheville, I took a tour of the Lake Eden campus that was home to BMC from the ’40s onward. Those lakeside college buildings that everyone with an interest in BMC will recognize are now used as a children’s summer camp, but the iconic study block, and the dining hall where Cunningham danced his monkey dance in 1948’s Ruse of Medusa, and where Theater Piece No. 1 was staged in 1952, remain exactly as they were. Visiting your site of interest in person is also important, because even when you’ve studied it in text or photos, often a very different impression can be gained from the size of the actual place, its atmosphere and so on.

BMC is outside Black Mountain, itself a small rural town in North Carolina, and a serious shortfall of funds meant giving up on having buildings designed by the likes of Marcel Breuer and Walter Gropius, and instead having the students help erect buildings designed by Lawrence Kocher. It was the kind of place where, due to the dining hall being the only large indoor space, Cunningham would clean it himself every day after breakfast, put the chairs and tables away to the side and give dance lessons, and where Buckminster Fuller’s first geodesic dome was a huge failure—not even managing to stand up—on a grassy area next to the college buildings (close I suspect to where there were fields at the time). There is something very encouraging in knowing such things happened here. Naturally it is true that BMC had a fairly unique network of people behind it, and attracted attention from various quarters even at the time, but the reality was that there was never enough money, there were constant disputes within the community, and amid all this, in order to get things done a great deal was improvised as they went along. This really hits home when you visit the actual campus and stand in that slightly gloomy dining hall block: the word “function” so beloved of Cage takes on a different kind of reality. And the fact that so many things emerged from this hands-on, faintly amateurish setting means a lot to those of us used to laying newspaper on our kitchen table or bedside to make works.

So this is how I’ve been spending my time in the United States—hopefully it comes in useful to someone for something. And I wonder right now, whether my time spent like this as an artist in the United States (while succumbing to frequent and intense bouts of righteous indignation of a different sort to that of Nagai Kafu), might also be the beginning of something.

The end

Technical notes for a stateside sojourn, plus a little extra (1)Technical notes for a stateside sojourn, plus a little extra (2)

Technical notes for a stateside sojourn, plus a little extra (3)

Technical notes for a stateside sojourn, plus a little extra (4) part 1

Kanai Manabu

Artist. Born in Tokyo in 1983. After his graduation from Jiyu Gakuen College, he received his Master’s degree from Institute of Advanced Media Arts and Sciences (IAMAS) and his PhD from Tokyo University of the Arts. He is Currently working in New York with the support of the Agency for cultural Affairs’ Program of Overseas Study for Upcoming Artists.