Artist-in-Residence (2):

AIR —Encounters with place, unique dialog-driven expression, cross-cultural respect and understanding

By Hinuma Teiko

My first contact with the unfamiliar realm of the AIR was in early 1990 while working as a gallery assistant after graduation. As I spent my days in equal part bewitched and befuddled by my first contemporary art-related job, the gallery was organizing consecutive exhibitions by three contemporary Japanese sculptors, and my encounter with one of these artists, Tsuchiya Kimio, [*1] was to alter the course of my life significantly. Tsuchiya’s works and personality possessed, at least to me, a distinctive aura that dispelled all my previous notions of sculpture and sculptors, an aura best summarized I suppose as “a whiff of the exotic.”

After spending time in the UK from 1981 to ’83, in 1989 Tsuchiya completed a master’s degree at the Chelsea School of Art, and received a grant from the British Council. During 1990–91 his work was exhibited alongside that of artists including Endo Toshikatsu, Kasahara Emiko, Kawamata Tadashi, and Toya Shigeo in “A Primal Spirit: Ten Contemporary Japanese Sculptors” at the Hara Museum and Los Angeles County Museum of Art, an exhibition that showcased for overseas audiences some outstanding examples of Japanese artistic expression. Tsuchiya then continued to take part in numerous sculpture projects and exhibitions in the UK and further afield, including in France, Belgium, Canada, and Norway, works and activities emerging from his experience of the AIR system and how it inspired him earning particular acclaim internationally, culminating in an honorary award and degree from the London Institute (now University of the Arts London) in 1999.

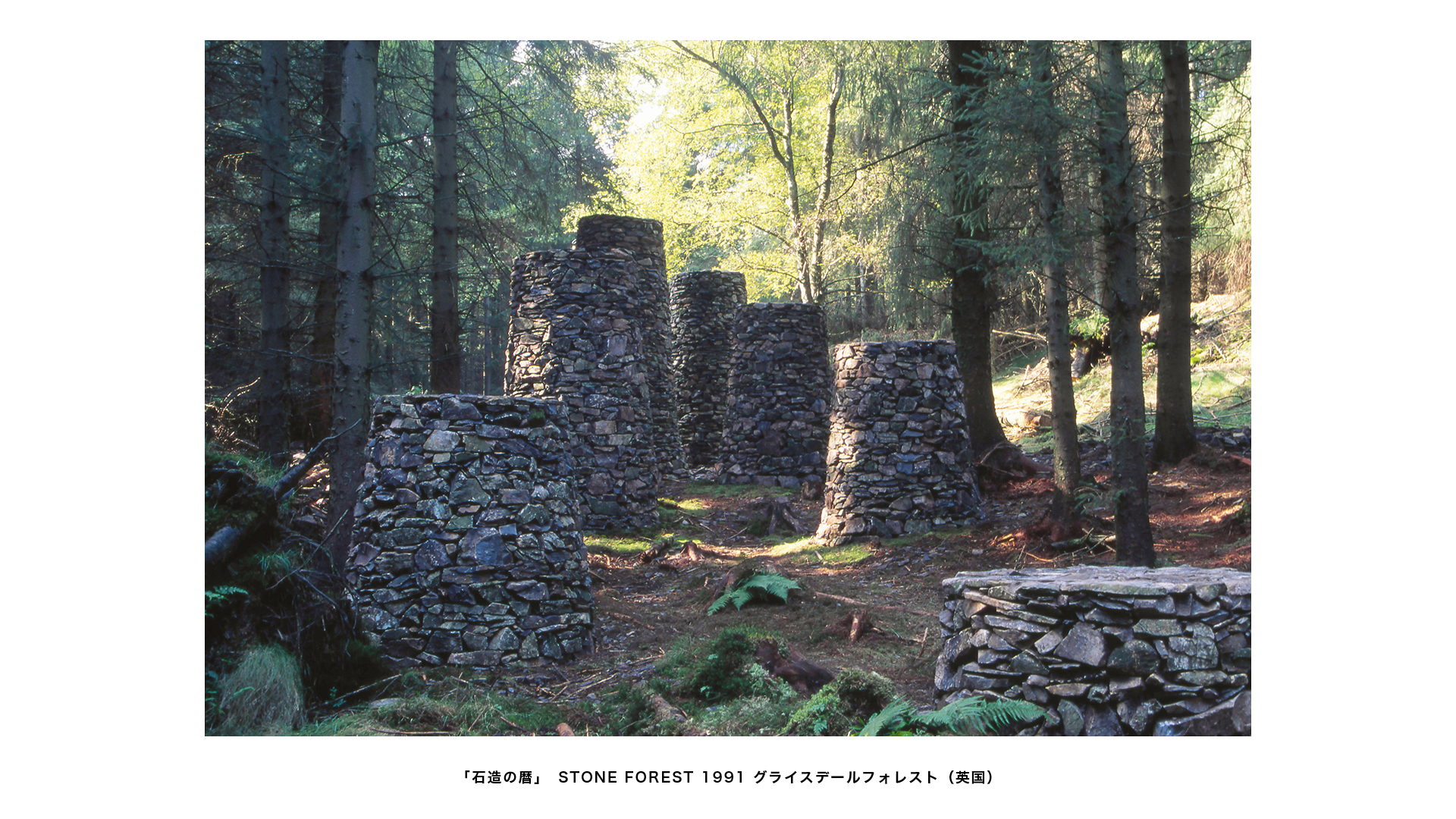

Returning to the gallery: during the preparations for Tsuchiya’s exhibition, sitting in on discussions as the most junior member of staff I was fascinated by his many tales of overseas experience, in particular time spent making art as an artist-in-residence, and the places in which he did so. At a castle in Limoges, France; in a forest near Antwerp, Belgium; Tsuchiya travels around gathering materials associated with a particular place, and working with people in that place to create a site-specific—in other words one-of-a-kind—piece of art. His descriptions of working on the Grizedale Forest Sculpture project, located in England’s Lake District, home of the National Trust movement and Beatrix Potter of Peter Rabbit fame, made a particularly vivid impression, the whole idea having the air of a modern-day fairytale.

Descended from a conservation movement supported by local donations and gifts that started in the late 19th century following the Industrial Revolution, by attracting people seeking encounters with sculptures by talented local and international artists installed in this lovely woodland, the Grizedale Forest Sculpture project not only encourages greater understanding of environmental issues, but contributes to the local economy. An AIR scheme operating here supports artists staying medium- to long-term to make their works in the forest. There are however some important rules. Artists are not permitted to fell trees or undertake any earthworks in order to acquire materials or a location to install their work. Nor may they erect any signs in the forest, or install captions. Works must also be constructed from materials that will weather and decay over time, eventually reverting to nature. Before serving as “art,” works must act as guardian deities of a sort for those traveling through the forest. I was impressed by an approach that linked art to the relationship between humans and nature, and saw art as inherent to nature’s path to revival, without denying past damage wrought by man’s domination, and made up my mind to visit Grizedale one day.

It turned out the opportunity to do just that would come rather earlier than expected. After those three solo exhibitions, the gallery where I worked was forced to close for various reasons, leaving me a free agent after less than a year in the job. Fortunately, thanks to the efforts of the gallery director I was able to secure another position. Finding myself with time before starting this new job, I was able to spend a couple of months staying with a friend in London. My life in the British capital consisted of weekday mornings at language school (though making little progress), and afternoons pottering around art museums, galleries, and theaters. Looking back on that time now, I truly was living the dream. One weekend I finally made that trip to Grizedale Forest.

After three- hour train journey from Euston to Windemere, I noticed that the people getting on and off at this station nearest to Grizedale were all equipped with rucksacks and climbing boots, ready to spend a weekend in the Lake District. Having planned this as a day trip from the capital, in that instant I realized my mistake (or rather, that my research had been somewhat lacking). But I figured I was here now, so duly hired a taxi and headed for the Forest Museum. Transported by the gobsmacked (at my ignorance, but nevertheless very kind) driver, I arrived to find what was indeed a big, tree-filled, bona fide forest. It was too late to go back now, so telling the driver the time of my return train, I made him promise to come back for me. When I said at the visitors’ center that I’d come from Japan to see Tsuchiya Kimio’s work, the person there kindly praised me for coming so far, and uttering something along the lines of, “Um, I think it’s around here somewhere,” pointed at a map. With this as my guide, I plunged into this vast expanse of woodland.

Any qualms I might have had about walking alone on a narrow path deep in the forest were thankfully dispelled by the presence of hikers I passed along the way. Taking heart from their cheerful greetings, finally, just before sunset I arrived at Tsuchiya’s tranquil, understated « Stone Forest ». The landscape in this region retaining a strong imprint of Celtic culture is crisscrossed by dry stone walls built to enclose sheep pastures, and apparently, learning of a long stretch of such wall destroyed by falling forest tees in a storm a few years earlier, Tsuchiya decided to use this stone for his work. Just like the ancient Celts before him, he determinedly stacked one stone upon another in the forest, to make a place for the marking of time. In any case, I can only say that I was lucky, in that pre-mobile era, to make my way safely out of that forest amid the gathering dusk. That I did so with such nonchalance was doubtless due to the obliviousness of youth.

Tsuchiya Kimio

Tracing an AIR experience of Tsuchiya Kimio’s during my studies in Britain gave me my own vicarious taste of the AIR experience. It may only have been a very small adventure, but the side order of solitude that comes with living in another country for a short time, and my encounters with new scenes and friendly, generous people, were for me a big experience, one that brought great personal growth, and different to the experience of a student exchange. But back then I had no way of knowing that a future of AIR involvement had already opened up for me. (To be continued)

[*1] Tsuchiya Kimio (b. 1955). Taking location and memory as themes, Tsuchiya employs waste from demolished houses, ash etc. in site-specific sculptures, monuments and works of public art that mark a particular place and the memories of its people, presenting these at contemporary art exhibitions worldwide, and during periods as an artist-in-residence. His academic posts to date include professor at Aichi University of the Arts, visiting professor at Musashino Art University, and visiting professor at Nihon University College of Art. Among his many awards are the 3rd Asakura Fumio Award in 1990, Grand Prize at the 14th Contemporary Japanese Sculpture Exhibition Grand Prize (Ube/Yamaguchi) in 1991, and an honorary award and degree from the London Institute (now UAL) in 1999. Numerous works by Tsuchiya are also held in public collections in Japan and elsewhere.AIR (1): A place that guarantees freedom, safety and diversity, and inspires artists.

AIR (3): Perspectives on the transmission of culture, AIR, and sustainability

AIR (4): The eyes of a pilot drifting through the world

AIR (5): Natural disaster and AIR—Rikuzentakata (1)

AIR (6): Natural disaster and AIR—Rikuzentakata (2)

AIR (7): Networks that connect with the world, AIRs that connect to the future

Hinuma Teiko

Professor at Joshibi University of Art and Design, head of the AIR Network Japan Preparatory Committee, Art Director at Tokiwa Museum. Hinuma worked at the preparatory office to establish the Aomori Contemporary Art Centre from 1999 and served as a curator there until 2011, providing support for artists, primarily through residencies for artists, and planning and running various projects and exhibitions. She has filled various other positions including Project Director of the Saitama Triennale 2016 and Program Director of the Rikuzentakata AiR Program.