Artist-in-Residence (6):

Natural disaster and AIR—Rikuzentakata (2)

By Hinuma Teiko

◉ Decoding and documenting personal encounters, history and landscapes

Rikuzentakata in November is a place of deepening chill as autumn turns to winter, and the landscape changes from day to day. Under stunning blue skies, the strong sea winds peculiar to Japan’s Pacific coast whip across the plains, while distant mountains wear a dusting of snow. Wild animals begin to haunt human settlements, seeking sustenance ahead of the long cold season, and flocks of swans fly in to winter over in wetland areas. To people here, these are familiar scenes that mark the start of every winter. For these hardy inhabitants of the north, they signal the arrival of the harshest time of year, but also invaluable time to spend with close family and friends, nestled in the cozy glow of home, awaiting the much-anticipated arrival of spring. In March 2011, just before the arrival of that spring once again, a disaster of unprecedented proportions snatched away this modest slice of happiness. Part of the natural cycle, best described as a sub-species of nature even, humans here have employed hands and knowledge to fashion a particular way of life, nurturing it over centuries into a distinctive, persistent, regional culture. But nurtured amidst the might of nature, a culture ephemeral, fragile. And all the more precious for it.

In November 2013, two years and eight months after catastrophe struck, we launched an AIR program in tsunami-devastated Rikuzentakata. The project involves creative activities grounded in research conducted by the artists and their interactions with the local community, in accordance with the theme “Rikuzentakata Artist-in-Residence—Landscape of Memories for Reminiscent Future.” It is an attempt to weave a “landscape of memories” of those who have called this place home over the generations. As mentioned in the previous instalment, great care was taken in selecting the artists. In a situation where almost all the local people affected by the disaster were still stuck in temporary housing, we envisaged that rather than artists leaving works of a material nature as products of their time here, records of the past and present of this place would be given visual form as a “landscape of memories,” through the bodies and gaze and experiences of the individual artists as they spent time alongside people, and that this “landscape of memories” might sow a tiny seed for imagining the future. Thus from a pool of trusted artists we already knew well, we approached Dutch photographer Leo van der Kleij, dancer and choreographer Sioned Huws from Wales, and multimedia artist Jaime Jesus C. Pacena II from the Philippines, and a three-month residency program was launched.

Series of photographs by Leo van der Kleis “Everyday life in Rikuzentakata” photo: Leo van der Kleis

Leo van der Kleij is an Amsterdam-based photographer who employs documentary techniques in expression based on personal observations of society. Leo had already spent considerable time in Japan over the years, and was known as an experienced artist more than capable of adapting flexibly to life in a disaster zone. During his stay he made it a daily habit to walk around Rikuzentakata taking photos. The kind of person who will chat to anyone, he easily found his way into the living rooms of those in temporary housing and gained permission to record their lives. In the central city with its piles of debris, in parallel with the removal of this debris, a massive effort to raise the ground level had also begun. Huge dump trucks drove around, picking up dust and dirt, which mixed with the snow that was starting to fall, turned to mud that coated the streets. The entire town was one giant set of earthworks as far as the eye could see, but those earning a living in that town were still people, doing what people do. Van der Kleij posted a sign saying “Daily life in Rikuzentakata” in a prefab in part of the town’s temporary shopping center, and there established a gallery which he updated daily, using it as a base to mix with those there to do their shopping.

Series of photographs by Leo van der Kleis “Everyday life in Rikuzentakata” photo: Leo van der Kleis

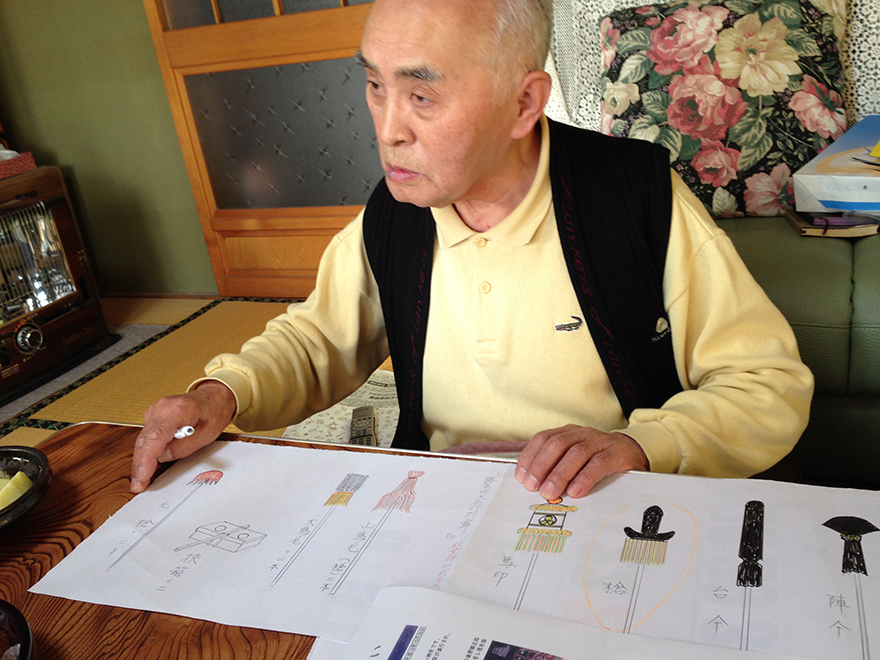

London-based Sioned Huws spent a month making work at ACAC in 2009 on assignment from the Chapter art center.[*1] While there she developed a strong interest in the traditional art of Tsugaru te-odori (Tsugaru hand dance), and since then has undertaken several ACAC residencies in order to explore the fundamental nature of dance, with its ability to cross time and borders. I have learned much from her meticulous research, always undertaken with the greatest of respect; her gaze, and the dedication with which she approaches her expression. It was with this deep trust that I harbored high hopes Huws would not only observe the city of Rikuzentakata, but turn her attention to the wider Tohoku region, and express the value of its culture from her own unique perspective. I suggested that during her research she make her way from Fukushima to Iwate, across the Tohoku area, moving north. In Iwaki she embarked on a dialogue with dancers and musicians of the Jangara nenbutsu odori (Jangara Buddhist invocation dance) and Shishi-mai (lion dance). In Rikuzentakata, while encountering traditional performing arts like the Daimyo gyoretsu-mai (Daimyo parade dance) and Hikami daiko (Hikami drums), what she valued most was socializing with the women who congregated at the Minna-no-Ie (Home-for-All) community center.[*2] Chatting while drinking tea or doing crafts, from time to time learning the local bon-odori dance or a song, she spent a large part of her time in the company of these women, in the process coming to understand the way songs and dances suffuse everyday routines in this community, and how indispensable they are to people’s very existence. The relationship between the women and Huws was to endure long after her time in the city, in strong bonds of friendship.

[*1] Community arts center in Cardiff, Wales (opened 1971), containing a gallery, cinema, theater, creative studio, and cafe.[*2] Community center built in the town of Rikuzentakata, which was devastated by the Tohoku quake and tsunami of 2011. Jointly designed by Ito Toyo, Inui Kimiko, Hirata Akihisa, and Sou Fujimoto, and completed in November 2012, the year after the disaster. At the 13th International Architecture Exhibition of the Venice Biennale, the Japan Pavilion won a Golden Lion, the highest award at the event, for its exhibit showing the processes involved in the design and construction of Minna-no-Ie. The project also attracted global attention. Dismantled in 2016 as ground elevation work proceeded, it was rebuilt in 2022 in the new town center.

Sioned Huws with local women, gathered at “Minna-no-Ie” to dance the Bon Odori “Rikuzentakata Ondo” dance|photo: Matsuyama Jun

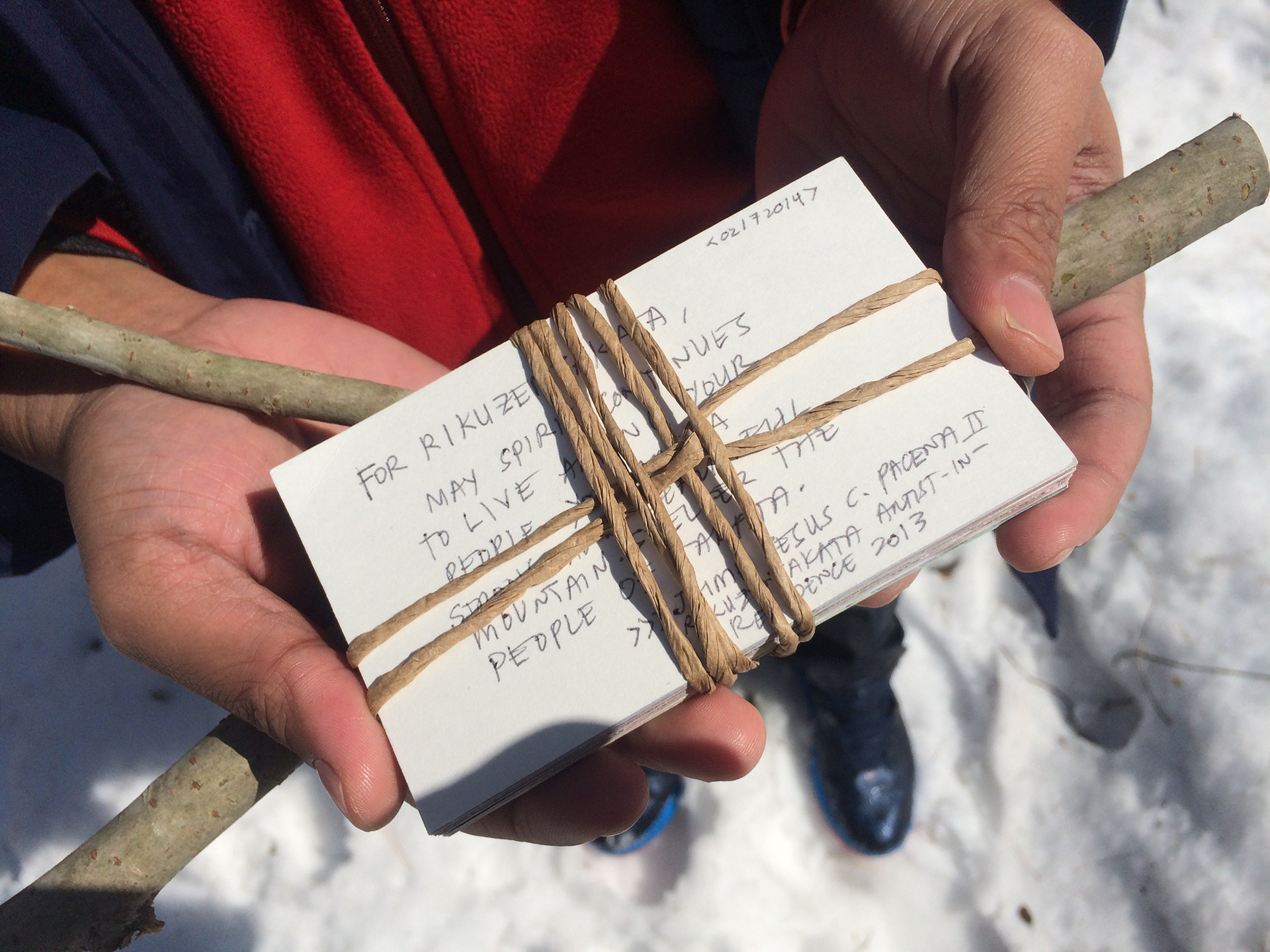

After his first stint in Japan, on a two-month internship at ACAC in 2000 as part of the JENESYS Program sponsored by the Japan Foundation, [*3] Jaime Pacena II took part in a study tour run as an adjunct to the Asahi Art Festival held soon after the Tohoku quake and tsunami. [*4] These two intimate experiences of the region were to build the foundations of mutual trust for his residency in Rikuzentakata. Pacena captured in photographs and video nature as it was after the disaster in sea and mountains, the former city center with its massive earthworks, and the lives of people in the dormitory where he stayed, and in temporary housing, in a project encompassing the environment in which he found himself as a visitor, and his dialogue with people’s memories. Meeting Rikuzentakata-based singer-songwriter Konno Masatoshi (a.k.a. Matto) also led to the making of a music video for Konno’s track 3.11 The Last Century.

[*3] The Invitation Program for Creators, part of the JENESYS Programme Japan-East Asia Network of Exchange for Students and Youth. Around 20 up-and-coming creators up to the age of 35 from 13 countries in the Asia-Pacific region are invited each year to take part in AIRs of 1–3 months in duration, hosted by Japanese institutions that run artist-in-residence programs, and other cultural institutions, with support provided for artists’ activities during their stay, presenting outcomes, and associated projects.[*4] Study tour taking in the Tohoku area after the quake and tsunami. Run as part of the World Network Project organized to mark ten years of the Asahi Art Festival (sponsored by Asahi Beer), with one creator each invited from seven countries in Asia.

Music video shooting by Jaime Jesus C. Pacena Ⅱ|photo: Matsuyama Jun

The program was a first, and to some extent made up as we went along, but after it ended a local supporter said to me, “When you go to a famous art museum, look at famous pictures, then treat yourself to some delicious food before heading home, obviously you will have had a splendid time. But there are artists who take snapshots of our day-to-day lives and call this art. We become part of that art. Which is something you can’t experience at an art museum.” These words have been a huge incentive for me to persist with our activities in Rikuzentakata. The original three artists were followed by more artists, and curators, from Armenia, Indonesia, Thailand, and Latvia, taking up residencies and engaging in activities in which learning about the natural environment, day-to-day life, and centuries-old culture, as well as mixing with people, are pivotal. After each three-month AIR stint ends I travel to centers such as Tokyo or Yokohama for the presentation of works, and to where the various artists were based, taking part in exhibitions, talks, dance performances, and art festivals, and through these, connect the achievements of those particular residencies to the next phase. During the pandemic in 2020, out of desperation we also engaged in remote AIRs to ensure that the artists forced to stay home, and the people of Rikuzentakata, would not be isolated but could maintain their connection. Thus I keep the enterprise that is the AIR program going, while carefully observing changes in the disaster zone over the years, and the international situation, and continually asking myself what I can do for both artists and local community. And without realizing I now find ten years have passed, and this place has become a home away from home both for the artists, and for me, a place we cannot do without.

Research by Sioned Huws in Rikuzentakata|photo: Matsuyama Jun

◉ Bonds between people, and manifestations of hope

Rikuzentakata is a town that unexpectedly gained world renown by its apocalyptic destruction. On first setting eyes on the “Miracle Pine Tree” [*5] restored and erected as a symbol of recovery from the tsunami, Pacena made the striking comment that the tree was not so much a miracle, as a manifestation of hope. Meaning that if we are to survive we need to have hope, rather than wait for miracles. What AIRs offer for artists are the inspiration that emerges from new encounters, and in turn, new openings for creating. But most important perhaps is the strong form of trust that arises between visitor and host. The truth and value at our very feet, unearthed by the presence of the artist, and the rediscovery of their beauty: I believe that when we interrogate what is precious to humans, and what it means to live a better life, sustained interaction and creative activity can generate tiny glimmers of hope that illuminate the world.

Plans are currently underway for Pacena to make a feature-length film as a result of his research and practice to date. If this film in which we place our hopes for the Philippines and Japan, and Rikuzentakata, proceeds smoothly, it will make its appearance this summer. Past, present, and as yet unseen future, every individual being and their memories, will continue to connect to the world.(To be continued)

[*5] Pine tree monument and remnant of the Tohoku quake located on the remains of the Takata Matsubara pine grove in Kisencho, Rikuzentakata.AIR (1): A place that guarantees freedom, safety and diversity, and inspires artists

AIR (2): AIR —Encounters with place, unique dialog-driven expression, cross-cultural respect and understanding

AIR (3): Perspectives on the transmission of culture, AIR, and sustainability

AIR (4): The eyes of a pilot drifting through the world

AIR (5): Natural disaster and AIR—Rikuzentakata (1)

AIR (7): Networks that connect with the world, AIRs that connect to the future

Hinuma Teiko

Professor at Joshibi University of Art and Design, head of the AIR Network Japan Preparatory Committee, Art Director at Tokiwa Museum. Hinuma worked at the preparatory office to establish the Aomori Contemporary Art Centre from 1999 and served as a curator there until 2011, providing support for artists, primarily through residencies for artists, and planning and running various projects and exhibitions. She has filled various other positions including Project Director of the Saitama Triennale 2016 and Program Director of the Rikuzentakata AiR Program.